Skip to main content

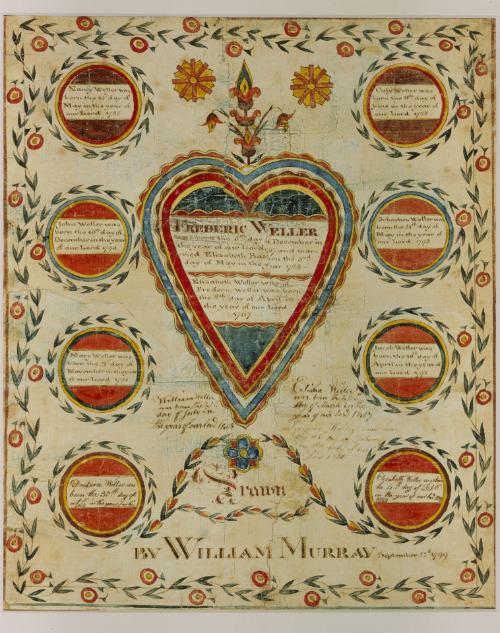

This delicately worked comb is a remarkable representative of this rare and unusual style. Geometric form dominates, and the visual texture of nucleated circles is distributed about the heavily-pierced rectangular face of the comb. The man standing in the central piercing is very Salish in pose and style, similar to a number of free-standing human figures in wood or bone collected in Salish territory (c.f. Holm 1987, p. 51, fig. 12; p. 53, fig. 13). The straightness of this man's stance echoes that of other Coast Salish human figures, including the triple piercings that set the arms apart from the body and separate the legs. Perhaps the most similar are carvings that originate among the Puget Sound Salish, speakers of the Lushootseed language, (c.f. Holm 1987, pp. 49, 51, 53, figs. 11,12,13) or Quinault (c.f. Holm 1983b, p. 30, fig. 23). The face sculpture is simplicity itself: a flattened oval is cut straight across by the browline, and small, round eyes are set closely within the hollowed area on either side of the nasal ridge. This nose ridge and round lips are left on the surface, along with a broad line on either side of the face defining a cranial structure of temple, cheek, and jawbone. The resultant hollow of the eyesocket extends down between the cheekbones to surround the lips, creating a typically Salishan positive-negative kind of graphic and an unexpectedly expressive face.

The figure's front is undecorated except for two nucleated circles which mark the heart and navel power points of the man's spirit. Circles also accent the shoulder and hip joints and the heart or belly of two animal images that form a delicate finial to the piece. This use of circles in Salishan art as power points or body joints appears to be drawn from an ancient human tradition that lies at the heart of all Northwest Coast style graphics, and is the essence of the structure around which the northern Northwest Coast formline tradition developed (Holm 1987, pp. 52, 56; Brown 1995, chapter 5) Very much akin to the form of the animal image on the handle of the Wasco/Wishxam horn ladle (see fig.T147), and the wolves of the Skokomish basketry tradition (see fig.T153), these two figures with angled tails may also represent wolves, a very prominent power animal in the southern coastal region. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceTaylor A. Dale, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographySotheby's. 22 & 24 October 1983, lot 306, property of a private collector.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.308.

Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2006, pg. 68.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 325.

Culture

Coast Salish

Comb

Date1800-1850

DimensionsOverall: 5 × 2 3/4 × 1/4 in. (12.7 × 7 × 0.6 cm)

Object numberT0152

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextExamples of very early southern Coast Salish artwork are quite rare in museum and private collections today. Coast Salish society motivated the creation of decorated objects in a very different way than was the case on the northern coast. Northern cultures were very stratified societies, and the crest emblems of family and clan were carved on a huge variety of objects made for public display, to acknowledge the ownership of historic traditions. Salish societies hold the belief that images represent personal power acquired through guardian spirits, and that power is diluted by the over-exposure of its source (Suttles 1983, p. 87). Partly as a consequence, the number of highly-decorated Salish pieces are few and their images rather cryptic.This delicately worked comb is a remarkable representative of this rare and unusual style. Geometric form dominates, and the visual texture of nucleated circles is distributed about the heavily-pierced rectangular face of the comb. The man standing in the central piercing is very Salish in pose and style, similar to a number of free-standing human figures in wood or bone collected in Salish territory (c.f. Holm 1987, p. 51, fig. 12; p. 53, fig. 13). The straightness of this man's stance echoes that of other Coast Salish human figures, including the triple piercings that set the arms apart from the body and separate the legs. Perhaps the most similar are carvings that originate among the Puget Sound Salish, speakers of the Lushootseed language, (c.f. Holm 1987, pp. 49, 51, 53, figs. 11,12,13) or Quinault (c.f. Holm 1983b, p. 30, fig. 23). The face sculpture is simplicity itself: a flattened oval is cut straight across by the browline, and small, round eyes are set closely within the hollowed area on either side of the nasal ridge. This nose ridge and round lips are left on the surface, along with a broad line on either side of the face defining a cranial structure of temple, cheek, and jawbone. The resultant hollow of the eyesocket extends down between the cheekbones to surround the lips, creating a typically Salishan positive-negative kind of graphic and an unexpectedly expressive face.

The figure's front is undecorated except for two nucleated circles which mark the heart and navel power points of the man's spirit. Circles also accent the shoulder and hip joints and the heart or belly of two animal images that form a delicate finial to the piece. This use of circles in Salishan art as power points or body joints appears to be drawn from an ancient human tradition that lies at the heart of all Northwest Coast style graphics, and is the essence of the structure around which the northern Northwest Coast formline tradition developed (Holm 1987, pp. 52, 56; Brown 1995, chapter 5) Very much akin to the form of the animal image on the handle of the Wasco/Wishxam horn ladle (see fig.T147), and the wolves of the Skokomish basketry tradition (see fig.T153), these two figures with angled tails may also represent wolves, a very prominent power animal in the southern coastal region. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceTaylor A. Dale, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographySotheby's. 22 & 24 October 1983, lot 306, property of a private collector.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.308.

Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2006, pg. 68.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 325.

On View

Not on viewca. 1810