Skip to main content

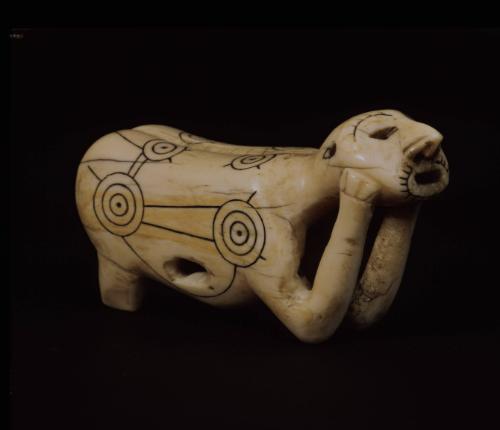

The human is depicted in an emaciated state, ribs bulging and thighs lacking of muscular bulk. This condition is another common metaphor for the shaman's ability to transcend death. The figure's arms were long ago broken off at the elbows, and the split surfaces since have been worn very smooth. The bear's jaws appear to be tearing the flesh from the skull, yet its front paws rest on the human's shoulders in an almost paternal fashion, and the human's pose reveals no sign of a struggle. This is a symbolic battle, not a literal one, a spiritual metaphor of transformation.

The carving of the bear itself is very straightforward and naturalistic, with minimal employment of the flat-design stylizations of Tlingit art. A round, abalone-inlaid ovoid defines the hind leg joint, and very square U-shapes are incised into the sides of the body. U-shapes on the strong, thick neck seem to represent wrinkles or folds in the skin. This spare use of an archaic style of flat-design is part of what suggests the age of this undocumented piece. A section of musket barrel from the early trade period forms the pipe bowl, and the wood appears to be walnut, which perhaps would have come from the stock of the same altered or repurposed firearm. It has been suggested that gun materials were used to associate their power of life and death with the pipes, which were primarily used during memorial rituals.

Tlingits at one time cultivated a rare species of tobacco (nicotiana quadrivalvis) that was mixed with lime from burned clam shells as a form of snuff. This was most likely nicotiana quadrivalvis, interestingly the same annual strain of the plant that the Apsaalooke (Crow) of Montana cultivated for tobacco ties. The importation of smoking tobacco (nicotiana rustica) by sailors from the eastern United States began early in the trade period, The traditional uses of tobacco as a sacramental prelude to ceremonial gatherings were continued with the new variety and its important smoking receptacle, the pipe. Possibly owned most likely by a shaman, this example may have been used in conjunction with healing ceremonies. The wear and polish of the surfaces that developed over time on many of these pipes are testimony to their long history and respectful place within the traditional culture. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceGeorge Terasaki, New York City

BibliographyMaurer, Evan M. The Native American Heritage: A Survey of North American Indian Art. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1977, p. 290, fig. 440.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.36.

Grambo, Rebecca L. Bear: A Celebration of Power and Beauty. Burlington, Vermont: Verve, 2000, p.110.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 412.

Culture

Tlingit

Pipe

Date1790-1830

DimensionsOverall: 3 7/8 × 1 5/8 × 4 in. (9.8 × 4.1 × 10.2 cm)

Object numberT0200

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Label TextThis small tobacco pipe is unusual for the complex piercing in its design, as well as for its overtly shamanic theme. The vast majority of Northwest Coast pipes are carved as clan crest animal images. In this case, a large bear is shown in the apparent act of devouring a human being, a common symbol for the spiritual transformation of a shamanic initiate. The bear is a very potent shamanic image throughout the temperate forests of the northern Pacific Rim, where the bear is the largest carnivore in existence. For many Asiatic and Native American groups, it is the most powerful of shaman's spirits. The symbolic denouement by the bear is the crossing of the boundary of death, into the world of spirit. It is here that the shaman's healing and visionary work is done, in the "shadow" of the visible world, and his ability to return from that state is what makes the shaman's power unique.The human is depicted in an emaciated state, ribs bulging and thighs lacking of muscular bulk. This condition is another common metaphor for the shaman's ability to transcend death. The figure's arms were long ago broken off at the elbows, and the split surfaces since have been worn very smooth. The bear's jaws appear to be tearing the flesh from the skull, yet its front paws rest on the human's shoulders in an almost paternal fashion, and the human's pose reveals no sign of a struggle. This is a symbolic battle, not a literal one, a spiritual metaphor of transformation.

The carving of the bear itself is very straightforward and naturalistic, with minimal employment of the flat-design stylizations of Tlingit art. A round, abalone-inlaid ovoid defines the hind leg joint, and very square U-shapes are incised into the sides of the body. U-shapes on the strong, thick neck seem to represent wrinkles or folds in the skin. This spare use of an archaic style of flat-design is part of what suggests the age of this undocumented piece. A section of musket barrel from the early trade period forms the pipe bowl, and the wood appears to be walnut, which perhaps would have come from the stock of the same altered or repurposed firearm. It has been suggested that gun materials were used to associate their power of life and death with the pipes, which were primarily used during memorial rituals.

Tlingits at one time cultivated a rare species of tobacco (nicotiana quadrivalvis) that was mixed with lime from burned clam shells as a form of snuff. This was most likely nicotiana quadrivalvis, interestingly the same annual strain of the plant that the Apsaalooke (Crow) of Montana cultivated for tobacco ties. The importation of smoking tobacco (nicotiana rustica) by sailors from the eastern United States began early in the trade period, The traditional uses of tobacco as a sacramental prelude to ceremonial gatherings were continued with the new variety and its important smoking receptacle, the pipe. Possibly owned most likely by a shaman, this example may have been used in conjunction with healing ceremonies. The wear and polish of the surfaces that developed over time on many of these pipes are testimony to their long history and respectful place within the traditional culture. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceGeorge Terasaki, New York City

BibliographyMaurer, Evan M. The Native American Heritage: A Survey of North American Indian Art. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1977, p. 290, fig. 440.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.36.

Grambo, Rebecca L. Bear: A Celebration of Power and Beauty. Burlington, Vermont: Verve, 2000, p.110.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 412.

On View

Not on view