Skip to main content

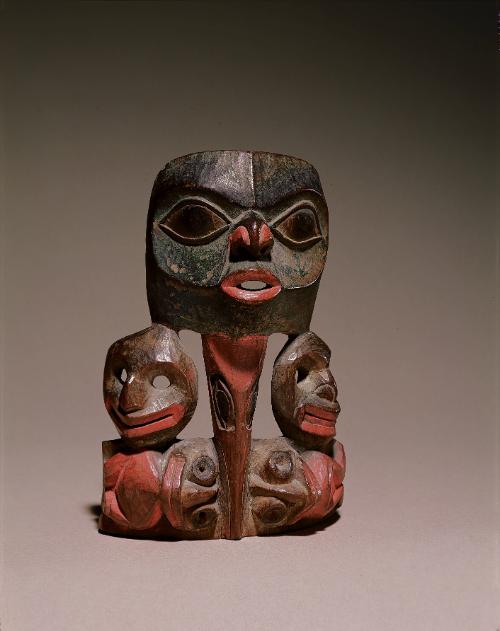

The body form of the birds, with their drawn-in wings and feet and arched necks, is the common central image of these shaman's accompaniments, though each of the rattles in existence has, for the most part, a completely different sculptured scene on the bird's back. Some commonalties exist in these representations, such as the orientation of the figures toward the handle (and therefore the holder) of the rattle, and the depiction of shamanic imagery: torturing witches, spirit travel, and the shaman's yeik (or spirit helpers) are frequent portrayals. Almost always seen is the image of a large, transformational being (often with long, curving horns) at the handle end of the assemblage, on or with which the other characters appear to be traveling.

This rattle has the typically graceful form of the oystercatcher's body and neck, an extremely delicate configuration with respect to the woodgrain orientation through the curve of the neck. The sculptural forms in the faces of the figures are distinctly Tlingit in style, and when compared with the nature of the flat-design structures employed about the rattle, the two aspects suggest that the rattle was carved in the last quarter of the 19th century. The faces on the bird's breast lack the traditional formline structure (only its sculptural relief has been retained), and certain aspects of color use are out of the ordinary, such as the blue applied to the positive ovoid shape at the shoulders of the wings. During the late 1800s, the conventions of the two-dimensional design tradition were in disintegration, largely resulting from the effects of mid-19th century disease epidemics and the general suppression of traditional culture. This meant that fewer people were receiving the old-style training and apprenticeship in the art traditions, and many new expressions and revisions of older conventions were seeing their appearance. Perhaps because the sculptural forms are more outwardly reproducible, these styles seemed to endure much longer without major alteration in general appearance. The flat-design, however, being so inwardly structured and dependent upon a relatively fragile network of relationships between forms and colors for its character, flow, and ability to convey depth and movement, tended to be much less readily absorbed without esoteric training, which had been denied by the loss of a generation of its finest practitioners.

The figures on this rattle appear to depict the head of a bear in the position of the more common sea monster/transformation figure. Emmons collected the rattle from Angoon, where the brown bear is one of the more prominent clan emblems. The nearly-always-present horns seen on these rattles have been appended to the bear's head, giving it a supernatural quality. The human has his tongue in contact with the bear's head, a symbol of the exchange of spiritual intimacy and knowledge. This oystercatcher is missing the frequently-seen bird's legs and anus on the bottom of the rattle, and the eye and face designs on the breast of the bird have more the character of the formline faces on the breast of raven rattles (T205) than the majority of the oystercatcher type. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceLt. George T. Emmons, collected at Angoon village, Southeast Alaska, c. 1900; Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (11/1760), New York, 1922; Edward Primus, Hollywood, California, exchanged from Heye Foundation, 1957; Kathryn White, Seattle; Ruth and George C. Kennedy, Los Angeles; Tambaran Gallery, New York City, 1982; Stefan Edlis, Chicago, Illinois

BibliographyLee 1979, cat. no. 8.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.383.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 437.

Rattle

Date1870-1890

DimensionsOverall: 3 3/4 × 6 1/4 × 15 1/2 in. (9.5 × 15.9 × 39.4 cm)

Object numberT0205

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Label TextOne of a type of rattle that appears to have been exclusively used by Tlingit shamans, the design is based on the body language of the black oystercatcher, a fairly common shorebird of the outer, seaward reaches of the shorelines throughout the Northwest Coast. The birds stand and walk in a very upright attitude, their black heads and red beaks carried at right angles to their long necks and bright red legs. The only time they assume the curvaceous, swan-like posture represented in these rattles is during a rare performance that may be a courtship dance or other body-language expression. At those times their necks arch up and down in wave-like motions of the kind that has been frozen in the rattle image.The body form of the birds, with their drawn-in wings and feet and arched necks, is the common central image of these shaman's accompaniments, though each of the rattles in existence has, for the most part, a completely different sculptured scene on the bird's back. Some commonalties exist in these representations, such as the orientation of the figures toward the handle (and therefore the holder) of the rattle, and the depiction of shamanic imagery: torturing witches, spirit travel, and the shaman's yeik (or spirit helpers) are frequent portrayals. Almost always seen is the image of a large, transformational being (often with long, curving horns) at the handle end of the assemblage, on or with which the other characters appear to be traveling.

This rattle has the typically graceful form of the oystercatcher's body and neck, an extremely delicate configuration with respect to the woodgrain orientation through the curve of the neck. The sculptural forms in the faces of the figures are distinctly Tlingit in style, and when compared with the nature of the flat-design structures employed about the rattle, the two aspects suggest that the rattle was carved in the last quarter of the 19th century. The faces on the bird's breast lack the traditional formline structure (only its sculptural relief has been retained), and certain aspects of color use are out of the ordinary, such as the blue applied to the positive ovoid shape at the shoulders of the wings. During the late 1800s, the conventions of the two-dimensional design tradition were in disintegration, largely resulting from the effects of mid-19th century disease epidemics and the general suppression of traditional culture. This meant that fewer people were receiving the old-style training and apprenticeship in the art traditions, and many new expressions and revisions of older conventions were seeing their appearance. Perhaps because the sculptural forms are more outwardly reproducible, these styles seemed to endure much longer without major alteration in general appearance. The flat-design, however, being so inwardly structured and dependent upon a relatively fragile network of relationships between forms and colors for its character, flow, and ability to convey depth and movement, tended to be much less readily absorbed without esoteric training, which had been denied by the loss of a generation of its finest practitioners.

The figures on this rattle appear to depict the head of a bear in the position of the more common sea monster/transformation figure. Emmons collected the rattle from Angoon, where the brown bear is one of the more prominent clan emblems. The nearly-always-present horns seen on these rattles have been appended to the bear's head, giving it a supernatural quality. The human has his tongue in contact with the bear's head, a symbol of the exchange of spiritual intimacy and knowledge. This oystercatcher is missing the frequently-seen bird's legs and anus on the bottom of the rattle, and the eye and face designs on the breast of the bird have more the character of the formline faces on the breast of raven rattles (T205) than the majority of the oystercatcher type. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceLt. George T. Emmons, collected at Angoon village, Southeast Alaska, c. 1900; Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (11/1760), New York, 1922; Edward Primus, Hollywood, California, exchanged from Heye Foundation, 1957; Kathryn White, Seattle; Ruth and George C. Kennedy, Los Angeles; Tambaran Gallery, New York City, 1982; Stefan Edlis, Chicago, Illinois

BibliographyLee 1979, cat. no. 8.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.383.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 437.

On View

Not on view