Skip to main content

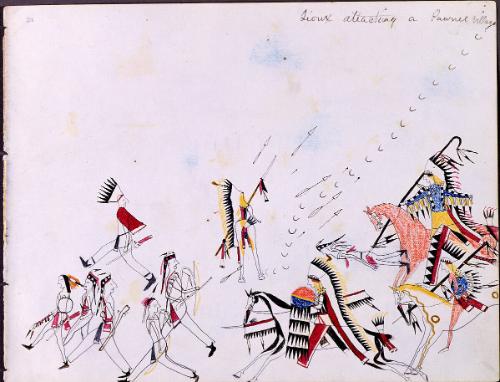

Scenes of personal bravery achieved during battle are a common subject in many Plains Indian drawings. The tribal affiliation of both the antagonist and protagonist can usually be identified by their dress, hair style, and implements; sometimes these clues can also provide insight into which military society those depicted belonged to. This drawing features three related scenes of combat, implying that they may have taken place during the same battle. All three mounted warriors are victors, although one of the warrior’s horses has received fatal battle wounds.

The mounted warrior at the top of the page wears a shirt fringed with ermine tails, shown by the vertical lines that extend from his arm; we know they are ermine because the artist included a dark spot at the end of each fringe, which represents the black tip of an ermine’s tail. The warrior is also wearing hair extenders, illustrated by the grouping of lines that hang from the back of his head. Many Apsaalooke (Crow) warriors wore hair extenders—stripes of hair that were tied to a leather thong and worn to give the warrior the appearance of very long hair. This warrior wears a pair of trade-cloth leggings and a shirt, both decorated with a pattern of black-and-white beading, which is often attributed to Aspaalooke warriors. His enemy is Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee), illustrated by his distinctive tribal hair style, face paint, and moccasins.

The scene found on the middle of the page shows a warrior who has dismounted and is attacking his enemy with a lance. The horse has received two fatal wounds, which have passed through his neck, shown by the lines that start from the enemy’s gun and travel through the horse. Fatal wounds are usually indicated when the victim bleeds from the mouth and nose. This warrior also wears an ermine tail fringed shirt and leggings, both decorated with black-and-white beading patterns. His enemy is clearly Apsaalooke. In many drawings and paintings, Apsaalooke warriors are shown with a pompadour, the upper half of the face painted red, and powder horn sash, which is also decorated with Apsaalooke beaded designs.

The clothing worn by the mounted warrior featured at the lower portion of the page is similar to the outfits of other mounted warriors. Both his fringed shirt and leggings are decorated with black-and-white beaded patterns and ermine tails. He carries a shield and wears a horned headdress with a long eagle-feathered trailer, which was used by many Plains tribes. As in the first scene, the mounted warrior is attacking a Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee), who is identified by his hair style and dress.

The drawing raises a few questions regarding tribal affiliations of those represented and, according to the style of the drawing, the tribal affiliation of the artist. Based on their clothing, the mounted warrior could be Apsaalooke, but that premise conflicts with the warrior on foot in the middle of the page who appears to be Apsaalooke. There were other tribes who wore ermine tail-fringed shirts and leggings, but not many who also wore hair extenders.

Another method of assigning tribal affiliation to an artist is to assess the drawing style. Apsaalooke drawings are usually highly stylized, most have sharp line and provide limited detail. Compared to other examples, this drawing is similar to works produced by Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) artists. Many Tsitsistas/Suhtai artists include meticulous details and had a clean, crisp style.

Analyzing the iconography of drawings with the hope of producing strong conclusions can be disconcerting, despite all the research. Every year more and more scholarly research is being published, making available new and important information about the artists and their works. But as we move forward into our own understanding of Plains Indian representational art, we must accept that the meaning of some drawings and paintings will only be known by those who produced them. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Joe Horse Capture

Exhibition History"American Treasures from the Fenimore Art Museum," Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, FL, February 20, 2004 - April 11, 2004.

ProvenanceMilwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Bernard Brown, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; George Terasaki, New York City; Don Ellis, Dundas, Ontario

BibliographyGeorge Terasaki advertisement [detail]. American Indian Art Magazine. Vol. 2, No. 3 (Summer 1977): 1.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.115.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 128.

Possibly

Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne)

Drawing - Two Bear's War Record

Datec. 1870

DimensionsSight: 23 × 17 7/8 in. (58.4 × 45.4 cm)

Object numberT0480

Credit LineGift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextThere have been many studies devoted to understanding the visual language of Plains Indian pictographs. The first comprehensive study, Colonel Garrick Mallery’s “Picture Writing of the American Indians,” appeared in the Tenth Annual Report of Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1888-89, and was published in 1893. Mallery’s publication combined the work of explorers, ethnologists, and researchers who visited reservations and provided valuable insight about Indian pictographic art in North America. In 1939, Dr. John Ewer’s Plains Indian Painting interpreted the forms and symbols of pictographs. By studying dozens of examples, Dr. Ewers compared style and content in order to understand what event the artist was recording. For ledger drawings, Karen Petersen’s Plains Indian Art from Fort Marion, published in 1971, was the first complete study that carefully examined and analyzed works on paper produced in the latter half of the 19th century by men who had been incarcerated at the fort. Petersen’s work also included a pictographic dictionary, a valuable tool that features illustrations of Plains Indian accoutrements and their attributions. Interpreting Plains Indian paintings and drawings without referencing these two valuable books is difficult.Scenes of personal bravery achieved during battle are a common subject in many Plains Indian drawings. The tribal affiliation of both the antagonist and protagonist can usually be identified by their dress, hair style, and implements; sometimes these clues can also provide insight into which military society those depicted belonged to. This drawing features three related scenes of combat, implying that they may have taken place during the same battle. All three mounted warriors are victors, although one of the warrior’s horses has received fatal battle wounds.

The mounted warrior at the top of the page wears a shirt fringed with ermine tails, shown by the vertical lines that extend from his arm; we know they are ermine because the artist included a dark spot at the end of each fringe, which represents the black tip of an ermine’s tail. The warrior is also wearing hair extenders, illustrated by the grouping of lines that hang from the back of his head. Many Apsaalooke (Crow) warriors wore hair extenders—stripes of hair that were tied to a leather thong and worn to give the warrior the appearance of very long hair. This warrior wears a pair of trade-cloth leggings and a shirt, both decorated with a pattern of black-and-white beading, which is often attributed to Aspaalooke warriors. His enemy is Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee), illustrated by his distinctive tribal hair style, face paint, and moccasins.

The scene found on the middle of the page shows a warrior who has dismounted and is attacking his enemy with a lance. The horse has received two fatal wounds, which have passed through his neck, shown by the lines that start from the enemy’s gun and travel through the horse. Fatal wounds are usually indicated when the victim bleeds from the mouth and nose. This warrior also wears an ermine tail fringed shirt and leggings, both decorated with black-and-white beading patterns. His enemy is clearly Apsaalooke. In many drawings and paintings, Apsaalooke warriors are shown with a pompadour, the upper half of the face painted red, and powder horn sash, which is also decorated with Apsaalooke beaded designs.

The clothing worn by the mounted warrior featured at the lower portion of the page is similar to the outfits of other mounted warriors. Both his fringed shirt and leggings are decorated with black-and-white beaded patterns and ermine tails. He carries a shield and wears a horned headdress with a long eagle-feathered trailer, which was used by many Plains tribes. As in the first scene, the mounted warrior is attacking a Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee), who is identified by his hair style and dress.

The drawing raises a few questions regarding tribal affiliations of those represented and, according to the style of the drawing, the tribal affiliation of the artist. Based on their clothing, the mounted warrior could be Apsaalooke, but that premise conflicts with the warrior on foot in the middle of the page who appears to be Apsaalooke. There were other tribes who wore ermine tail-fringed shirts and leggings, but not many who also wore hair extenders.

Another method of assigning tribal affiliation to an artist is to assess the drawing style. Apsaalooke drawings are usually highly stylized, most have sharp line and provide limited detail. Compared to other examples, this drawing is similar to works produced by Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) artists. Many Tsitsistas/Suhtai artists include meticulous details and had a clean, crisp style.

Analyzing the iconography of drawings with the hope of producing strong conclusions can be disconcerting, despite all the research. Every year more and more scholarly research is being published, making available new and important information about the artists and their works. But as we move forward into our own understanding of Plains Indian representational art, we must accept that the meaning of some drawings and paintings will only be known by those who produced them. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Joe Horse Capture

Exhibition History"American Treasures from the Fenimore Art Museum," Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, FL, February 20, 2004 - April 11, 2004.

ProvenanceMilwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Bernard Brown, Milwaukee, Wisconsin; George Terasaki, New York City; Don Ellis, Dundas, Ontario

BibliographyGeorge Terasaki advertisement [detail]. American Indian Art Magazine. Vol. 2, No. 3 (Summer 1977): 1.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.115.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 128.

On View

On view