Skip to main content

The prisoners sold these small drawing books to tourists vacationing at nearby St. Augustine. Their jailers circulated some to military men, such as General William Tecumseh Sherman, advocates of Indian rights and education, such as Bishop Henry Whipple, and historians, such as Francis Parkman (Berlo 1996a, pp. 115-117, cat. no. 45). Many intact books still exist in museums, archives, and in collections of descendants of the people who acquired them; others have been taken apart during the last 120 years and the drawings dispersed to various collections. This work and the one by Ohettoint are examples of the latter.

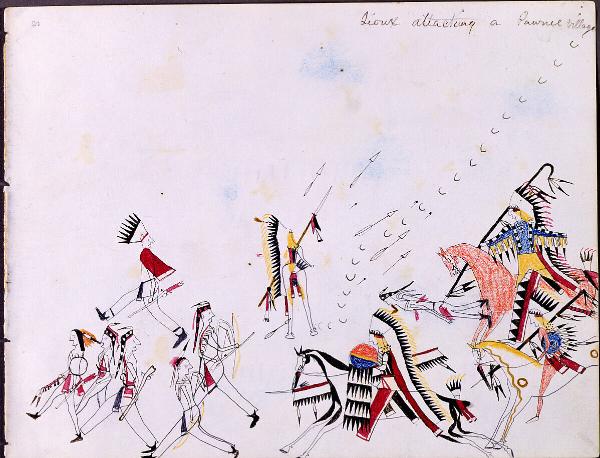

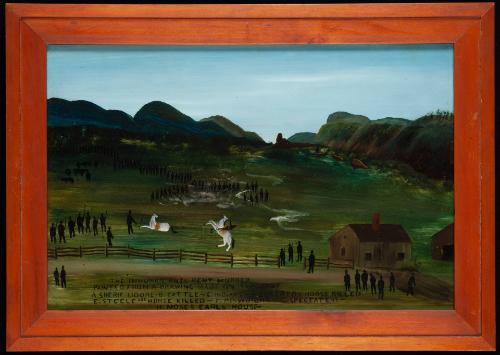

Chief Killer has drawn a vivid scene of combat in which three mounted warriors bear down upon six retreating Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee) who stride across the page, most of them looking back at their aggressors. Another Chahiksichahiks has fallen face down and is being speared by the crooked lance of the horseman at the upper right. A fourth warrior on horseback is depicted from the rear, in the middle of the page. His horse's hoofprints, which begin in the upper right, indicate that he rode into the action and then veered off to the right. Somewhat smaller than the other figures, he seems to be at some distance from them.

All of the horsemen carry implements of war. In addition to the crooked lance mentioned above, two men carry straight lances, and one wields a banner lance richly adorned with feathers down its entire length. The man on the right wears a fine example of a beaded war shirt with eagle feathers and locks of hair appended to the arms. Two of the high-ranking warriors carry painted shields. On the Great Plains, the painting on a shield was highly individualistic. A Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) would easily recognize the men depicted by the shield imagery. The two horses at the bottom of the page wear human scalp ornaments at their bridle bits. The artistic convention for this grisly war trophy is a circle, half black and half red, with hair hanging down from it.

The Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee) are scantily dressed in shirt breechcloths and distinctive Chahiksichahiks-style cuffed moccasins. One wears a bear claw necklace, while several sport otterskin war hats embellished with small round mirrors. Both the otter and the bear are animals imbued with sacred power, and wearing their body parts is believed to lend strength to men in war.

A notation of "21" is penciled in the upper left corner of the paper. There is no drawing on the reverse. On the upper right hand side of the page is written in pen "Sioux Attacking a Pawnee Village." While many of the Fort Marion drawings were captured by George Fox, the interpreter at the prison, his inscriptions were usually written in pencil, centered beneath the image. This inscription may be a later addition by the original owner of the book. Analysis of other inscriptions on late 19th-century Plains drawings has shown that such captions are often erroneous (Berlo 199a, pp. 76-79, 129 and pp. 210-15). While the enemies here may well be Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee), it is more likely that the heroes of the skirmish are the men of the artist's own Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheynne) tribe. In the Plains drawing tradition, the men customarily drew scenes of their own personal bravery and that of their families and comrades.

This drawing comes from a sketchbook, individual pages of which were sold through Morning Star Gallery in Santa Fe in 1990. Based on stylistic attributes, art historian Joyce Szabi has attributed all of the drawings to the Cheyenne artist Chief Killer (Szabi 1994b, p. 51). Anthropologist Imre Nagy, in an unpublished study of the entire Fort Marion book from which this drawing was removed, as well as a study of the work of Chief Killer, disputes this identification (Thaw Collection files). Another book of sixteen drawings done by Chief Killer at Fort Marion exists in the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection at the Brown University Library. Those drawings as well as this one show his characteristic faces, often devoid of features, and his distinctive way of drawing horses. Chief Killer was imprisoned because of his participation, along with a number of other Southener Tsitsistas/Suhtai, in an attack on a white family in Jansas in which the parents were killed and several children taken as captives. Upon his return to the West in 1878, Chief Killer worked as a butcher, policeman, and teamster. Noo artistic works are known by him that postdate his Fort Marion years (Peterson 1971, p. 234). (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed. Janet Catherine Berlo)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

"Treasures from the Thaw Collection," Wheelwright Museum of American Indian Art. Santa Fe, NM, May 1, 2000 - December 31, 2000.

ProvenanceGrandfather of Mrs. Dorothy Gieske, collected at Fort Marion, St. Augustine. Florida, in March 1876; Morning Star Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographyMorning Star Gallery/Parco ca. 1992, n.p.

Szabo, Joyce. "Chief Killer and a New Reality: Narration and Description in Fort Marion Art." American Indian Art Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 2, (Spring 1994): p.51 [mention of 10 Fort Marion drawings sold through Morning Star.]

Perriot, Francoise, Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, Somogy, editions d'Art, 1999, p. 50, fig. 36.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.119.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 131.

Artist

Chief Killer

(1849 - 1922 or an unidentified artist from Fort Marion)

Culture

Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne)

Drawing - Sioux Attacking Pawnee Village

Date1875-1876

DimensionsOverall (Image Dimensions): 8 3/8 × 11 in. (21.3 × 27.9 cm)

Framed: 15 3/4 × 19 1/4 × 3/4 in. (40 × 48.9 × 1.9 cm)

Object numberT0083

Credit LineGift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextDuring the years 1875-1878, some six dozen Kiowa, Tsitsistas/Suhati (Cheynne), Arapaho, and other prisoners from the Southern Plains were incarcerated at Fort Marion, Florida, accused of various crimes against white soldiers and settlers. Under the stewardship of Lieutenant Richard Pratt (1840-1924), they learned reading and writing, had religious instruction, and were allowed to earn money by making curios and filling small sketchbooks with drawings. The subject matter of Fort Marion drawings ranged from traditional scenes of warrior life on the Plains, such as this drawing attributed to Chief Killer, to scenes that depicted the unusual world that these prisoners encountered as they traveled by wagon, train, and boat far from Indian Territory to a stone fort on the Atlantic coast of Florida (Peterson 1971; Szabo 1994a; Berlo 1996a).The prisoners sold these small drawing books to tourists vacationing at nearby St. Augustine. Their jailers circulated some to military men, such as General William Tecumseh Sherman, advocates of Indian rights and education, such as Bishop Henry Whipple, and historians, such as Francis Parkman (Berlo 1996a, pp. 115-117, cat. no. 45). Many intact books still exist in museums, archives, and in collections of descendants of the people who acquired them; others have been taken apart during the last 120 years and the drawings dispersed to various collections. This work and the one by Ohettoint are examples of the latter.

Chief Killer has drawn a vivid scene of combat in which three mounted warriors bear down upon six retreating Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee) who stride across the page, most of them looking back at their aggressors. Another Chahiksichahiks has fallen face down and is being speared by the crooked lance of the horseman at the upper right. A fourth warrior on horseback is depicted from the rear, in the middle of the page. His horse's hoofprints, which begin in the upper right, indicate that he rode into the action and then veered off to the right. Somewhat smaller than the other figures, he seems to be at some distance from them.

All of the horsemen carry implements of war. In addition to the crooked lance mentioned above, two men carry straight lances, and one wields a banner lance richly adorned with feathers down its entire length. The man on the right wears a fine example of a beaded war shirt with eagle feathers and locks of hair appended to the arms. Two of the high-ranking warriors carry painted shields. On the Great Plains, the painting on a shield was highly individualistic. A Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) would easily recognize the men depicted by the shield imagery. The two horses at the bottom of the page wear human scalp ornaments at their bridle bits. The artistic convention for this grisly war trophy is a circle, half black and half red, with hair hanging down from it.

The Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee) are scantily dressed in shirt breechcloths and distinctive Chahiksichahiks-style cuffed moccasins. One wears a bear claw necklace, while several sport otterskin war hats embellished with small round mirrors. Both the otter and the bear are animals imbued with sacred power, and wearing their body parts is believed to lend strength to men in war.

A notation of "21" is penciled in the upper left corner of the paper. There is no drawing on the reverse. On the upper right hand side of the page is written in pen "Sioux Attacking a Pawnee Village." While many of the Fort Marion drawings were captured by George Fox, the interpreter at the prison, his inscriptions were usually written in pencil, centered beneath the image. This inscription may be a later addition by the original owner of the book. Analysis of other inscriptions on late 19th-century Plains drawings has shown that such captions are often erroneous (Berlo 199a, pp. 76-79, 129 and pp. 210-15). While the enemies here may well be Chahiksichahiks (Pawnee), it is more likely that the heroes of the skirmish are the men of the artist's own Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheynne) tribe. In the Plains drawing tradition, the men customarily drew scenes of their own personal bravery and that of their families and comrades.

This drawing comes from a sketchbook, individual pages of which were sold through Morning Star Gallery in Santa Fe in 1990. Based on stylistic attributes, art historian Joyce Szabi has attributed all of the drawings to the Cheyenne artist Chief Killer (Szabi 1994b, p. 51). Anthropologist Imre Nagy, in an unpublished study of the entire Fort Marion book from which this drawing was removed, as well as a study of the work of Chief Killer, disputes this identification (Thaw Collection files). Another book of sixteen drawings done by Chief Killer at Fort Marion exists in the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection at the Brown University Library. Those drawings as well as this one show his characteristic faces, often devoid of features, and his distinctive way of drawing horses. Chief Killer was imprisoned because of his participation, along with a number of other Southener Tsitsistas/Suhtai, in an attack on a white family in Jansas in which the parents were killed and several children taken as captives. Upon his return to the West in 1878, Chief Killer worked as a butcher, policeman, and teamster. Noo artistic works are known by him that postdate his Fort Marion years (Peterson 1971, p. 234). (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed. Janet Catherine Berlo)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

"Treasures from the Thaw Collection," Wheelwright Museum of American Indian Art. Santa Fe, NM, May 1, 2000 - December 31, 2000.

ProvenanceGrandfather of Mrs. Dorothy Gieske, collected at Fort Marion, St. Augustine. Florida, in March 1876; Morning Star Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographyMorning Star Gallery/Parco ca. 1992, n.p.

Szabo, Joyce. "Chief Killer and a New Reality: Narration and Description in Fort Marion Art." American Indian Art Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 2, (Spring 1994): p.51 [mention of 10 Fort Marion drawings sold through Morning Star.]

Perriot, Francoise, Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, Somogy, editions d'Art, 1999, p. 50, fig. 36.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.119.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 131.

On View

Not on viewc. 1922-1954

c. 1913

c. 1957

c. 1957