Skip to main content

Other traditions of dance and mythology may also have originated among the peoples of the north-central coast. The Wuikinuxv, Heiltsuk, and Kwakwaka`wakw all create masks and perform dances that represent a wild man of the woods, known as Bakwas in Kwak'wala. The concept may have originated among the Wuikinuxv. Sometimes called the cockle-hunter in English, the name describes the creature's fond habit of searching the beaches to find and eat the meat of these sweet-tasting bivalves. The Bakwas is said to be shy and of poor eyesight, and the performer will often back half-timidly into the dancing house, peeking over his shoulders from one side to the other. The outfit of a Bakwas dancer has varied from a skin-tight deerskin costume in the turn of the century era (Curtis 1914, vol. 10, pl. [XX] ,p. [XX]), while more contemporary dancers have performed in black cloth outfits hung with rows of hanging, white U-forms around their arms, torso, and legs.

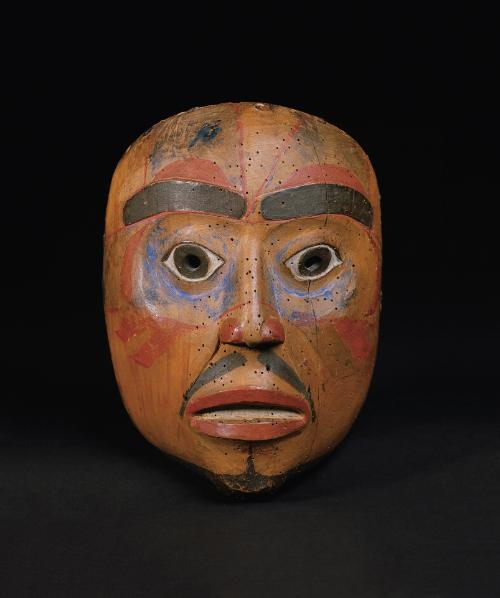

This mask appears to conform to attributes that are characteristic of the Heiltsuk interpretation of the Bakwas image (see Hilton 1990, p. 318, fig. 5b, a Heiltsuk version, pre-1902). A cockle-hunter mask in general usually features a heavy, protruding forehead; a hooked, beak-like nose; deep-set eyes; small, pointed ears and drawn-back lips, sometimes with teeth exposed. Heiltsuk masks of the Bakwas frequently convey a wart-hog like appearance, while the Wuikinuxv seem to model the image after a more cat-like facial quality (c.f. Hilton 1990, p. 318, fig. 5d; Hawthorn 1970, pp. 292-295; Mochon 1966, pp. 72, 88). The Kwakwaka`wakw versions of the image conform more closely to the Wuikinuxv concept of the wild man, though older, more naturalistically influenced Kwakwaka`wakw mask makers have sometimes focused on an emaciated, humanoid skull-like quality. Both types and their many cross-derivations are represented by contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw artists. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

ProvenanceCollected by Dorr Francis Tozier, US Revenue Service, c. 1890; Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (6/8808) in 1917, New York City; Julius Carlebach, New York City, in 1942; private collection, Midwest; Sotheby's, New York City, 1978; Frank Wood, New Bedford, Massachusetts; Sotheby's, New York City, 1987; Jonathan Holstein, Cazenovia, New York

BibliographySotheby's. 26 October 1978, Sale 4166, lot 294, Private Collection, Midwest.

Sotheby's. 2 December 1987, Sale 5643, lot 199, property of various owners.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.325.

Perriot, Francoise, and Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, Somogy edition d'Art, 1999, p. 118, fig. 93.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 344.

Culture

Heiltsuk (Bella Bella)

Bakwas "Cockle-hunter" Mask

Date1870-1880

DimensionsOverall: 11 × 8 1/4 in. (27.9 × 21 cm)

Object numberT0163

Credit LineGift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextMythological and ceremonial traditions among the Wakashan-speaking peoples of the Central Northwest Coast have a lot in common, and much evidence exists in corroboration with Native oral histories which describe the transfer of such traditions from the Heiltsuk-Oowekeeno to adjacent peoples, both north and south (Hilton 1990, pp. 318-319). The Kwakwaka`wakw, whose villages lie to the south of the Heiltsuk and who have been celebrated for their elaborate and enduring performance traditions, inherited many of their highest-ranking ceremonial complexes and privileges from the Heiltsuk and Wuikinuxv (Oowekeeno), including the Hamat'sa Society dances.Other traditions of dance and mythology may also have originated among the peoples of the north-central coast. The Wuikinuxv, Heiltsuk, and Kwakwaka`wakw all create masks and perform dances that represent a wild man of the woods, known as Bakwas in Kwak'wala. The concept may have originated among the Wuikinuxv. Sometimes called the cockle-hunter in English, the name describes the creature's fond habit of searching the beaches to find and eat the meat of these sweet-tasting bivalves. The Bakwas is said to be shy and of poor eyesight, and the performer will often back half-timidly into the dancing house, peeking over his shoulders from one side to the other. The outfit of a Bakwas dancer has varied from a skin-tight deerskin costume in the turn of the century era (Curtis 1914, vol. 10, pl. [XX] ,p. [XX]), while more contemporary dancers have performed in black cloth outfits hung with rows of hanging, white U-forms around their arms, torso, and legs.

This mask appears to conform to attributes that are characteristic of the Heiltsuk interpretation of the Bakwas image (see Hilton 1990, p. 318, fig. 5b, a Heiltsuk version, pre-1902). A cockle-hunter mask in general usually features a heavy, protruding forehead; a hooked, beak-like nose; deep-set eyes; small, pointed ears and drawn-back lips, sometimes with teeth exposed. Heiltsuk masks of the Bakwas frequently convey a wart-hog like appearance, while the Wuikinuxv seem to model the image after a more cat-like facial quality (c.f. Hilton 1990, p. 318, fig. 5d; Hawthorn 1970, pp. 292-295; Mochon 1966, pp. 72, 88). The Kwakwaka`wakw versions of the image conform more closely to the Wuikinuxv concept of the wild man, though older, more naturalistically influenced Kwakwaka`wakw mask makers have sometimes focused on an emaciated, humanoid skull-like quality. Both types and their many cross-derivations are represented by contemporary Kwakwaka'wakw artists. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

ProvenanceCollected by Dorr Francis Tozier, US Revenue Service, c. 1890; Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation (6/8808) in 1917, New York City; Julius Carlebach, New York City, in 1942; private collection, Midwest; Sotheby's, New York City, 1978; Frank Wood, New Bedford, Massachusetts; Sotheby's, New York City, 1987; Jonathan Holstein, Cazenovia, New York

BibliographySotheby's. 26 October 1978, Sale 4166, lot 294, Private Collection, Midwest.

Sotheby's. 2 December 1987, Sale 5643, lot 199, property of various owners.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.325.

Perriot, Francoise, and Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, Somogy edition d'Art, 1999, p. 118, fig. 93.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 344.

On View

Not on viewc. 1950