Skip to main content

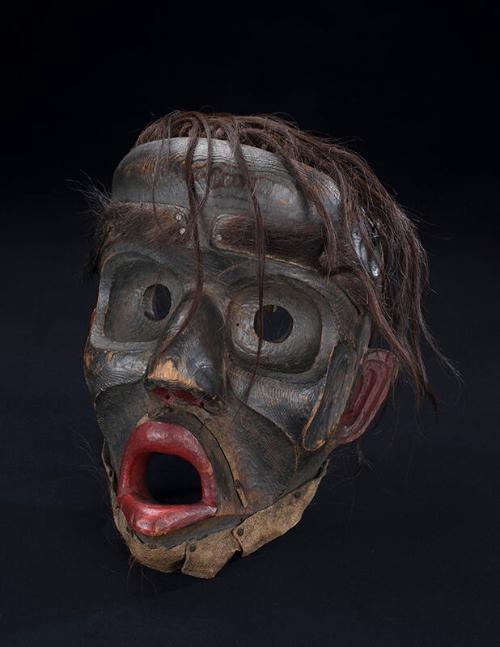

Such is the case with certain regions more than others. Not a large number of artifacts collected from the Haisla people can be found in the worldwide corpus of Northwest Coast art, due in part perhaps to the extreme isolation and relatively small population of the Haisla villages prior to the devastating period of epidemics. Among those that can be identified as Haisla or attributed on the basis of style, masterful pieces like this one cause one to imagine what wonders may have vanished without a trace. Only a handful of other masks have been attributed to the unknown maker of this striking piece of work (c.f. Sawyer 1983, p. 146), which by their development and refinement suggest that these must have been, but a fraction of the artist's full production. The earliest documented of these was seen and painted by Canadian artist Paul Kane at Fort Victoria in 1846, far from where it must have originated (Holm 1983b, p. 41). Creations by this artist other than masks may also exist to give a further glimpse of what his special vision once spawned.

The Haisla are the most northern of the Wakashan-language peoples, and their traditions speak of a convergence of Northern Wakashans and Coast Tsimshians. Marriages bwtween Haislas and the Gitksans of Gispakloats, the Coast Tsimshians of Kitkatla, and the Nuxalk/Heiltsuk of Kimsquit have intermingled cultural and artistic traditions in the region (Hamori-Torok 1990, p. 306). Northern-style matrilineal clan organization and Wakashan-style secret ceremonial societies have been melded together among the Haisla as a result of these unions.

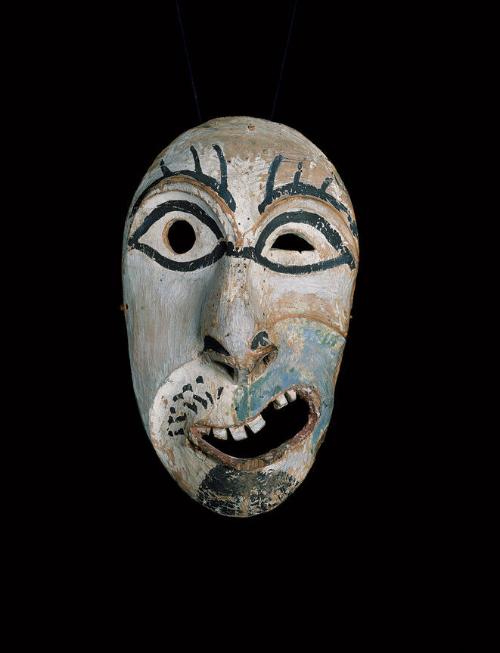

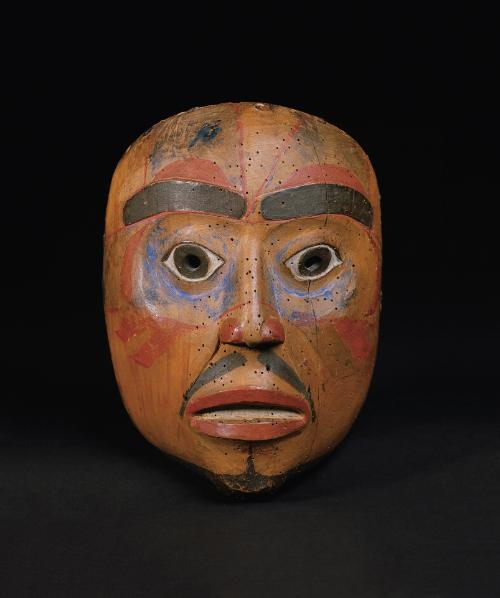

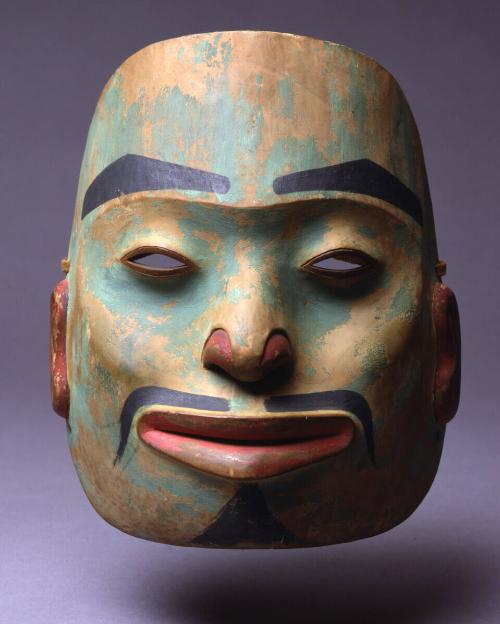

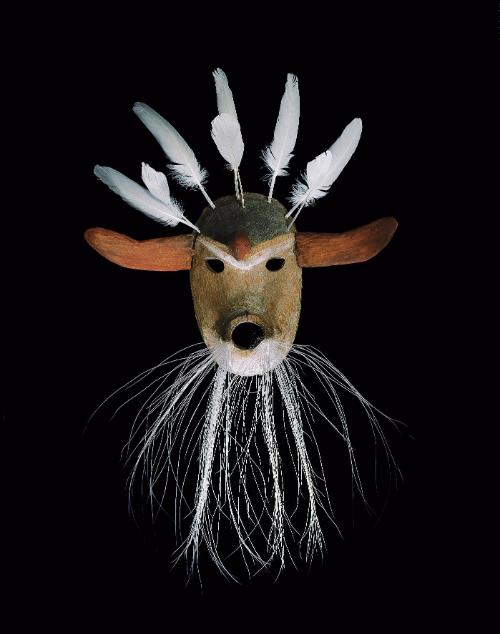

Such a commingling can also be seen among artistic traditions in the composition of this mask. The tendency toward soft planes and naturalistic junctures of many northern artists is blended very smoothly with a delicate variety of stylization based on the Southern Wakashan model. Within the half-cylinder of the overall form, ovoid-shaped eyesockets (a northern trait), enclose very unusually shaped eye and eyelid forms. The eyelids are so short and eccentric about the iris that they resemble the eyes of certain northern Tlingit mask-makers. The nose is narrow and very stylized, while the cheeks are full and convex, rolling in to the edges of the mouth in a compromisingly naturalistic fashion. The lips seem to emerge from within the bulge of the cheeks, and a stylized crease runs from there up to the nostrils. The thin-weight, elegantly balanced formlines painted on the face are a part of the mid-19th century, northern British Columbian mainland evolution, one of soft, round corners and open, airy design spaces. The orange stripe across the eyesocket may help to identify the image represented: Boas (1909) illustrated a number of Nuxalk masks, and recorded a name for one with a very similar stripe across the eyes as Xe'mtsiwa, herald of the dawn. The introduction of such Nuxalk traditions through marriage among the Haisla may have influenced this representation. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceMr. and Mrs. Alan Backstrom, Bothell, Washington; Jerrie and Anne Vander Houwen, Yakima, Washington; Morning Star Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.327.

Holm, Bill. Box of Daylight: Northwest Coast Indian Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1983, p. 41, no. 44, pp. 144-145, fig. 3b, p. 147.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 340.

Culture

Haisla

Mask

Date1840-1860

DimensionsOverall: 11 × 8 × 7 in. (27.9 × 20.3 × 17.8 cm)

Object numberT0166

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextOne of the frustrations inherent to the study of historic Northwest Coast art is that the surviving body of artwork from the entire region is only that--the survivors. No one can know how much of what was once made no longer exists, even from just the 19th century. Housefires, objects buried with their owners, deliberate destruction (missionaries have done their share), have all removed some proportion of the total record from that which survives. Occasionally, the size of the missing gaps becomes somewhat sadly apparent. The hand of an inspired and developed artist is recognized in but one or a few surviving masterpieces out of the probable dozens that the carver may have actually produced in their lifetime. Those that have departed can only be imagined.Such is the case with certain regions more than others. Not a large number of artifacts collected from the Haisla people can be found in the worldwide corpus of Northwest Coast art, due in part perhaps to the extreme isolation and relatively small population of the Haisla villages prior to the devastating period of epidemics. Among those that can be identified as Haisla or attributed on the basis of style, masterful pieces like this one cause one to imagine what wonders may have vanished without a trace. Only a handful of other masks have been attributed to the unknown maker of this striking piece of work (c.f. Sawyer 1983, p. 146), which by their development and refinement suggest that these must have been, but a fraction of the artist's full production. The earliest documented of these was seen and painted by Canadian artist Paul Kane at Fort Victoria in 1846, far from where it must have originated (Holm 1983b, p. 41). Creations by this artist other than masks may also exist to give a further glimpse of what his special vision once spawned.

The Haisla are the most northern of the Wakashan-language peoples, and their traditions speak of a convergence of Northern Wakashans and Coast Tsimshians. Marriages bwtween Haislas and the Gitksans of Gispakloats, the Coast Tsimshians of Kitkatla, and the Nuxalk/Heiltsuk of Kimsquit have intermingled cultural and artistic traditions in the region (Hamori-Torok 1990, p. 306). Northern-style matrilineal clan organization and Wakashan-style secret ceremonial societies have been melded together among the Haisla as a result of these unions.

Such a commingling can also be seen among artistic traditions in the composition of this mask. The tendency toward soft planes and naturalistic junctures of many northern artists is blended very smoothly with a delicate variety of stylization based on the Southern Wakashan model. Within the half-cylinder of the overall form, ovoid-shaped eyesockets (a northern trait), enclose very unusually shaped eye and eyelid forms. The eyelids are so short and eccentric about the iris that they resemble the eyes of certain northern Tlingit mask-makers. The nose is narrow and very stylized, while the cheeks are full and convex, rolling in to the edges of the mouth in a compromisingly naturalistic fashion. The lips seem to emerge from within the bulge of the cheeks, and a stylized crease runs from there up to the nostrils. The thin-weight, elegantly balanced formlines painted on the face are a part of the mid-19th century, northern British Columbian mainland evolution, one of soft, round corners and open, airy design spaces. The orange stripe across the eyesocket may help to identify the image represented: Boas (1909) illustrated a number of Nuxalk masks, and recorded a name for one with a very similar stripe across the eyes as Xe'mtsiwa, herald of the dawn. The introduction of such Nuxalk traditions through marriage among the Haisla may have influenced this representation. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceMr. and Mrs. Alan Backstrom, Bothell, Washington; Jerrie and Anne Vander Houwen, Yakima, Washington; Morning Star Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.327.

Holm, Bill. Box of Daylight: Northwest Coast Indian Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1983, p. 41, no. 44, pp. 144-145, fig. 3b, p. 147.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 340.

On View

Not on view