Skip to main content

Many of the oldest frontlets from the northern coast employ the inlay of abalone shell very sparingly, and often not at all on the flat rim that surrounds the central figure. Fine, regular, parallel grooves frequently texture the surface of these earliest rim plaques, seemingly a conservative hold-over from the era of beaver-tooth finishing tools. Usually painted in the typical pale blue of the northern palette, these textured rims have sometimes been inlaid with shell at a later date, when an increase in trade made the abalone shells easier to obtain. The Native pale, white abalone was rarely used for decorative inlay on the Northwest Coast. Haliotis Fulgens from California and Mexico was the preferred species because of its rich color and iridescence.

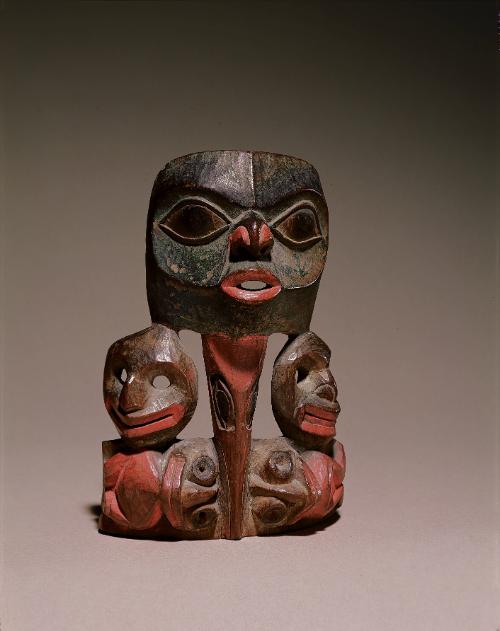

Compact frontlets with a single central image and grooved rims evolved over time to become more and more elaborate, and this fine example illustrates one trend in that development. One very early style of frontlet is composed of a squarish, formline-style face structure, relief-carved and sometimes surrounded by a bordering flat rim. Inlays, if they were included, are fitted into the eyes and other major design ovoids or circles. This concept, which may have been the prerogative of a certain clan or family line, became more and more complex through time to include richly inlaid, tiny faces in the eyes and ovoids of the central image, and often rows of small, subsidiary figures parallel to the rim around the outside of the main face. Each step in these developments occurred when an artist expanded the conceptual limits of what had been done before, providing inspiration to those who would see that work and in turn expand it further.

In this well-elaborated carving, the shape of the old single central image formline-face has been retained, but the figure is rendered in a naturalistic sculpture. The sensuously modeled face-perhaps a humanoid eagle-is framed by a wide pentagonal rim, reminiscent of the shape of the top of a copper, which, like the frontlet, is also a symbol of wealth. The rim has been densely inlaid with imported abalone shell. Tsimshian mythology may be the motivation behind the inclusion of numbers of small subsidiary figures as seen on totem poles, certain masks, and headdress frontlets. Here small frogs in a row seem to be pushing the upper rim border away from the eagle face with their hind feet, the thin cross-section of the frontlet pierced right through between the sides of their bodies and the rim. These frogs most likely figure in the background history of the depicted image, characters from the narrative story encapsulated in the carving.

Even more elaborate versions of this composite type of image have been made, in which subsidary figures completely surround the central face, sometimes in a double row. Each of the developmental steps owes it existence to the dreams and ideas of those who carved out the wat befire them, such as the maker of this inspiring ceremonial object. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

"Treasures from the Thaw Collection," Wheelwright Museum of American Indian Art. Santa Fe, NM, May 1, 2000 - December 31, 2000.

ProvenanceGeorge Terasaki, New York City

BibliographyMaurer, Evan M. The Native American Heritage: A Survey of North American Indian Art. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1977, p. 300, fig. 463.

Vincent, Gib. "The Eugene and Clare Thaw Collection of American Indian Art." The Magazine Antiques. (July 1995): cover.

"The Top 100 Collectors in America." Art & Antiques. March 1996, p.101.

Perriot, Francoise, and Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, somogy edition d'Art, 1999, p. 125, fig. 100.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.358.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 393.

Culture

Tsimshian

Possibly

Gitksan

Frontlet

Date1825-1850

DimensionsOverall: 6 5/8 × 6 × 2 in. (16.8 × 15.2 × 5.1 cm)

Object numberT0176

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextThe origin of the dancing headdress and its associated traditions have been placed by Native oral history at the Nass River in northern British Columbia (Swanton 1909, pp. 170-173). Examination of the existing artifactual record appears to corroborate this account. The frontlet concept spread outward from the Nass River to adjacent peoples through marriages or as gifts. A number of northern-made frontlets have been collected in the Kwakwaka`wakw villages, such as Alert Bay or Port Hardy (c.f. fig.T177 or Brown 1995, cat. X), demonstrating the migration of the tradition to that southern location.Many of the oldest frontlets from the northern coast employ the inlay of abalone shell very sparingly, and often not at all on the flat rim that surrounds the central figure. Fine, regular, parallel grooves frequently texture the surface of these earliest rim plaques, seemingly a conservative hold-over from the era of beaver-tooth finishing tools. Usually painted in the typical pale blue of the northern palette, these textured rims have sometimes been inlaid with shell at a later date, when an increase in trade made the abalone shells easier to obtain. The Native pale, white abalone was rarely used for decorative inlay on the Northwest Coast. Haliotis Fulgens from California and Mexico was the preferred species because of its rich color and iridescence.

Compact frontlets with a single central image and grooved rims evolved over time to become more and more elaborate, and this fine example illustrates one trend in that development. One very early style of frontlet is composed of a squarish, formline-style face structure, relief-carved and sometimes surrounded by a bordering flat rim. Inlays, if they were included, are fitted into the eyes and other major design ovoids or circles. This concept, which may have been the prerogative of a certain clan or family line, became more and more complex through time to include richly inlaid, tiny faces in the eyes and ovoids of the central image, and often rows of small, subsidiary figures parallel to the rim around the outside of the main face. Each step in these developments occurred when an artist expanded the conceptual limits of what had been done before, providing inspiration to those who would see that work and in turn expand it further.

In this well-elaborated carving, the shape of the old single central image formline-face has been retained, but the figure is rendered in a naturalistic sculpture. The sensuously modeled face-perhaps a humanoid eagle-is framed by a wide pentagonal rim, reminiscent of the shape of the top of a copper, which, like the frontlet, is also a symbol of wealth. The rim has been densely inlaid with imported abalone shell. Tsimshian mythology may be the motivation behind the inclusion of numbers of small subsidiary figures as seen on totem poles, certain masks, and headdress frontlets. Here small frogs in a row seem to be pushing the upper rim border away from the eagle face with their hind feet, the thin cross-section of the frontlet pierced right through between the sides of their bodies and the rim. These frogs most likely figure in the background history of the depicted image, characters from the narrative story encapsulated in the carving.

Even more elaborate versions of this composite type of image have been made, in which subsidary figures completely surround the central face, sometimes in a double row. Each of the developmental steps owes it existence to the dreams and ideas of those who carved out the wat befire them, such as the maker of this inspiring ceremonial object. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

"Treasures from the Thaw Collection," Wheelwright Museum of American Indian Art. Santa Fe, NM, May 1, 2000 - December 31, 2000.

ProvenanceGeorge Terasaki, New York City

BibliographyMaurer, Evan M. The Native American Heritage: A Survey of North American Indian Art. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1977, p. 300, fig. 463.

Vincent, Gib. "The Eugene and Clare Thaw Collection of American Indian Art." The Magazine Antiques. (July 1995): cover.

"The Top 100 Collectors in America." Art & Antiques. March 1996, p.101.

Perriot, Francoise, and Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, somogy edition d'Art, 1999, p. 125, fig. 100.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.358.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 393.

On View

Not on view