Skip to main content

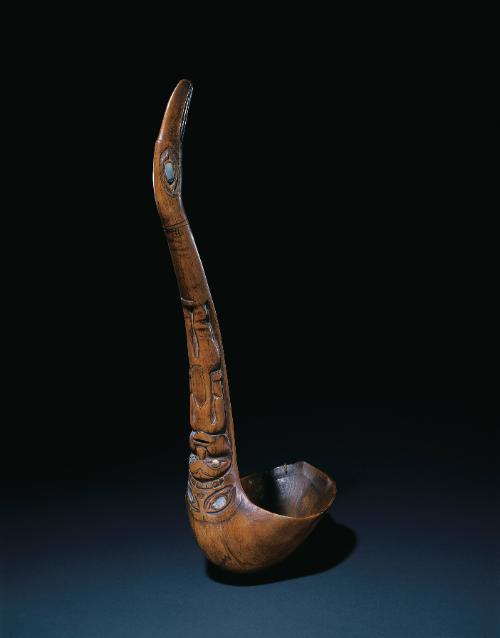

The rise of the ends sweeps farther upward than many others, so much so that the grease that saturates the lower levels of the bowl has not penetrated the higher extremes. The shallow groove found beneath the inner rim of many dishes has been repeated side by side, and the resulting broad band of tapered fluting fairly mimics the form of the dish. The interrelationship of seal and human has been illustrated by the addition of a relief-carved human figure beneath the seal's lower jaw. The image represents a person wearing the head of the seal as a mask, assuming its identity in the sharing of its life-energy. Such traits are not unique to this particular dish, but each demonstrates how new ideas and improvisations become part of the vocabulary of the tradition, to be drawn upon by succeeding artists (c.f. Sturtevant 1974, fig. 12).

The style of the sculpture and flat-design elements in the dish suggest a Haida origin, probably in the first half of the 19th century. Heavier formlines, smaller negative spaces, and a greater angularity of form mark the older, more conservative tradition, and some of those qualities are present here. Coupled with the degree of oil saturation and the blackened oxidation of the wood surface, these indications reveal that the grand Haida object must have been already antique when Mr. Dickerman came across it, and would have traveled some distance from where it was most likely made. Tlingit and Haida peoples had lived in close contact for a century since the migration of the Haida across the Dixon entrance into the formerly Tlingit-occupied villages of Dall, Long, and Prince of Wales Islands of the Alexander Archipelago. Such an heirloom object may have come to the northern Tlingit territory of Sitka as a gift between First Nations clan leaders. The generosity of a potlatch host often extended beyond the rich foods on which the guests feasted to include gifts of the dishes in which the meals were served. A number of such feast dishes, collected in the 1880s from the Haida villages of Masset and Skidegate on behalf of the Smithsonian, appear by the style of their work to have been made by Tlingit artists, evidently generations prior to their acquisition (c.f. Sturtevant 1974, figs.15 & 27).

In one manner or another this esteemed dish eventually became a part of the growing late-19th century market in artifacts. Sitka in 1883, in addition to being the capital of the newly American-owned Alaska Territory, had continued to be the center of trade and commerce established by the Russian-America Fur Company. The many shops and streetside curio-sellers that have been documented in photographs of the 1880s and 90s were the sources of many fine old objects for private and museum collectors from around the world. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"American Indian Art from the Fenimore Art Museum: The Thaw Collection," Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, NY, October 13, 2018 - December 31, 2018.

ProvenanceAlton L. Dickerman, collected in Sitka, Alaska, c. 1883; Miss Foster B. Dickerman, Colorado Springs, Colorado; Mrs. Alice Bemis Taylor, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1928; Taylor Museum (5159), Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1954

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert T. Masterpieces of American Indian Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995, p.77.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.338.

Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2006, pg. 160.

Douglas, Frederic H., and Rene d'Harnoncourt. Indian Art of the United States. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1941. Reprinted New York: Arno Press, 1969, (not ill.).

Gunther, Erna. Indians of the Northwest Coast. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1951, (not ill.).

Wardewell, Allen. Yakutat South Indian Art of the Northwest Coast. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1964, p. 55, cat. no. 122.

Duff, Wilson, Bill Holm, and Bill Reid. Art of the Raven. Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1967, n.p., cat. no. 139.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 365.

Culture

Haida

Dish

Date1820-1850

MediumAlder

DimensionsOverall: 7 1/4 × 10 1/2 × 15 1/2 in. (18.4 × 26.7 × 39.4 cm)

Object numberT0179

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextA very large and early seal-form dish, this example demonstrates the way a Northwest Coast sculptural tradition can be embellished and expanded upon without altering its essential core. carved serving bowls were meant to hold the seal or eulachon oil that was so valuable and important to the Native diet. This old and darkened grease dish displays the elaboration of many of its aspects, yet the basic essence of traditional seal- dish forms remain within it. The raised ends and outward-flaring sides of the unembellished dish type were maintained like a conceptual armature or theme on which to base an inspired improvisation, and this artist has developed many of the possibilities imaginable. The head and tail of the seal were carved with strong, massive qualities that echo the larger-than-average scale of this bowl. The rise of the ends sweeps farther upward than many others, so much so that the grease that saturates the lower levels of the bowl has not penetrated the higher extremes. The shallow groove found beneath the inner rim of many dishes has been repeated side by side, and the resulting broad band of tapered fluting fairly mimics the form of the dish. The interrelationship of seal and human has been illustrated by the addition of a relief-carved human figure beneath the seal's lower jaw. The image represents a person wearing the head of the seal as a mask, assuming its identity in the sharing of its life-energy. Such traits are not unique to this particular dish, but each demonstrates how new ideas and improvisations become part of the vocabulary of the tradition, to be drawn upon by succeeding artists (c.f. Sturtevant 1974, fig. 12).

The style of the sculpture and flat-design elements in the dish suggest a Haida origin, probably in the first half of the 19th century. Heavier formlines, smaller negative spaces, and a greater angularity of form mark the older, more conservative tradition, and some of those qualities are present here. Coupled with the degree of oil saturation and the blackened oxidation of the wood surface, these indications reveal that the grand Haida object must have been already antique when Mr. Dickerman came across it, and would have traveled some distance from where it was most likely made. Tlingit and Haida peoples had lived in close contact for a century since the migration of the Haida across the Dixon entrance into the formerly Tlingit-occupied villages of Dall, Long, and Prince of Wales Islands of the Alexander Archipelago. Such an heirloom object may have come to the northern Tlingit territory of Sitka as a gift between First Nations clan leaders. The generosity of a potlatch host often extended beyond the rich foods on which the guests feasted to include gifts of the dishes in which the meals were served. A number of such feast dishes, collected in the 1880s from the Haida villages of Masset and Skidegate on behalf of the Smithsonian, appear by the style of their work to have been made by Tlingit artists, evidently generations prior to their acquisition (c.f. Sturtevant 1974, figs.15 & 27).

In one manner or another this esteemed dish eventually became a part of the growing late-19th century market in artifacts. Sitka in 1883, in addition to being the capital of the newly American-owned Alaska Territory, had continued to be the center of trade and commerce established by the Russian-America Fur Company. The many shops and streetside curio-sellers that have been documented in photographs of the 1880s and 90s were the sources of many fine old objects for private and museum collectors from around the world. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"American Indian Art from the Fenimore Art Museum: The Thaw Collection," Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute, Utica, NY, October 13, 2018 - December 31, 2018.

ProvenanceAlton L. Dickerman, collected in Sitka, Alaska, c. 1883; Miss Foster B. Dickerman, Colorado Springs, Colorado; Mrs. Alice Bemis Taylor, Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1928; Taylor Museum (5159), Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1954

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert T. Masterpieces of American Indian Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995, p.77.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.338.

Jonaitis, Aldona. Art of the Northwest Coast. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2006, pg. 160.

Douglas, Frederic H., and Rene d'Harnoncourt. Indian Art of the United States. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1941. Reprinted New York: Arno Press, 1969, (not ill.).

Gunther, Erna. Indians of the Northwest Coast. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1951, (not ill.).

Wardewell, Allen. Yakutat South Indian Art of the Northwest Coast. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1964, p. 55, cat. no. 122.

Duff, Wilson, Bill Holm, and Bill Reid. Art of the Raven. Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 1967, n.p., cat. no. 139.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 365.

On View

Not on view