Skip to main content

The weaving of strong and aromatic fibers like spruce roots into volumetric containers such as this is a marvelously constructive art, in contrast to the reductive art of sculpture, where material substance is steadily removed to produce a finished product. A weaver begins with many bundles of fine, delicate strands that have no particular shape or volume. By the cyclic rotation of each row of twining she produces a strong, flexible fabric that has shape and encloses an interior void. Weaving from the center-bottom out and down to the edge of the basket, (Haidas weave these containers upside-down, Tlingits weave them right-side up), the woman who made this basket alternated the horizontal surface stitch between dyed and undyed weft strands to produce the upper and lower vertical dashing lines that border the two-strand woven field. Binding together weft to warp, stitch by stitch, the weaver need always be mindful of the even tension and control required to produce such a regular, straight-sided form as this. Rows of self-patterned, skip-stitch twining create the seemingly raised design of interconnected diamond shapes that embellishes the area just below the rim. Haida baskets for the most part (there are exceptions) do not employ separate added surface elements to create design patterns (such as the false embroidery of the Tlingit weavers; [T194, T195]), but rely on dyed weft strands to create encircling bands of color, and the self-patterned weaves to introduce a variety of textures to the basket fabric.

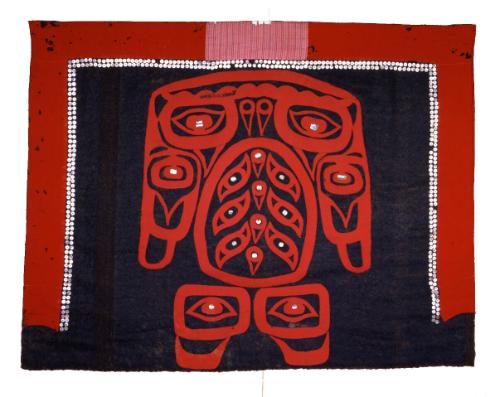

At least since the early 19th century, female Haida basketry artists have worked in concert with traditionally male artists who would paint crest-emblem designs on the smoothly-woven upper surface of spruce root hats (T193). Occasionally in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, men and women collaborated to create painted baskets like this one for sale to the outside market. The painting here represents a bear, wrapped around the plainly-woven field flanked by the dashed-line borders. The style of the painting is late 19th century, and matches a series of commissioned designs created by an artist named Tom Price for C.F. Newcombe, which are now in the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, B.C. The weaver of the hat may have been his wife, or perhaps a close female relative, who designed the open field to accept the painting by Price. Today similar collaborations once again complement one another in the production of elegantly-decorated weavings in basketry form. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Provenance de Menil Collection, Houston, Texas; Stefan Edlis, Chicago, Illinois

BibliographyHolm, Bill and William Reid. Form and Freedom. Texas: Rice University: Institute for the Arts, 1975, p.147, fig.51, de Menil Collection.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.353.

Grambo, Rebecca L. Bear: A Celebration of Power and Beauty. Burlington, Vermont: Verve, 2000, p.67.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 383.

Attributed to

Tom Price

(1857 - 1927, Haida)

Basket

Datec. 1880

MediumSpruce root, paint

DimensionsOverall: 12 × 13 3/4 in. (30.5 × 34.9 cm)

Object numberT0192

Credit LineGift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextSpruce-root baskets balance the beauty of finely-split roots and the detailed rhythm and orderly patterns of woven containers. The smooth outer surface of the peeled roots is retained to form the facing surface of the finished basket, which oxidizes to a warm, golden color over time. Spruce root baskets were used for a variety of purposes, from cooking (by the stone-boiling method), to berry gathering, to storage of dried foods or other goods. The requisite skills of gathering, peeling, splitting, and twining spruce were taught to young girls at the feet of their older female relative. Haida women excelled at the precision of preparation and the regularity of twined rows that produces the kind of quiet perfection seen in this beautifully woven example. The mid-20th century years of war, worldwide depression, and boarding-school assimilation took their toll on the inheritance of these skills by following generations of Haidas, but in recent decades new weavers have appeared in the footsteps of their grandparents who have developed the impressive skill levels of their predecessors.The weaving of strong and aromatic fibers like spruce roots into volumetric containers such as this is a marvelously constructive art, in contrast to the reductive art of sculpture, where material substance is steadily removed to produce a finished product. A weaver begins with many bundles of fine, delicate strands that have no particular shape or volume. By the cyclic rotation of each row of twining she produces a strong, flexible fabric that has shape and encloses an interior void. Weaving from the center-bottom out and down to the edge of the basket, (Haidas weave these containers upside-down, Tlingits weave them right-side up), the woman who made this basket alternated the horizontal surface stitch between dyed and undyed weft strands to produce the upper and lower vertical dashing lines that border the two-strand woven field. Binding together weft to warp, stitch by stitch, the weaver need always be mindful of the even tension and control required to produce such a regular, straight-sided form as this. Rows of self-patterned, skip-stitch twining create the seemingly raised design of interconnected diamond shapes that embellishes the area just below the rim. Haida baskets for the most part (there are exceptions) do not employ separate added surface elements to create design patterns (such as the false embroidery of the Tlingit weavers; [T194, T195]), but rely on dyed weft strands to create encircling bands of color, and the self-patterned weaves to introduce a variety of textures to the basket fabric.

At least since the early 19th century, female Haida basketry artists have worked in concert with traditionally male artists who would paint crest-emblem designs on the smoothly-woven upper surface of spruce root hats (T193). Occasionally in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, men and women collaborated to create painted baskets like this one for sale to the outside market. The painting here represents a bear, wrapped around the plainly-woven field flanked by the dashed-line borders. The style of the painting is late 19th century, and matches a series of commissioned designs created by an artist named Tom Price for C.F. Newcombe, which are now in the Royal British Columbia Museum, Victoria, B.C. The weaver of the hat may have been his wife, or perhaps a close female relative, who designed the open field to accept the painting by Price. Today similar collaborations once again complement one another in the production of elegantly-decorated weavings in basketry form. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Provenance de Menil Collection, Houston, Texas; Stefan Edlis, Chicago, Illinois

BibliographyHolm, Bill and William Reid. Form and Freedom. Texas: Rice University: Institute for the Arts, 1975, p.147, fig.51, de Menil Collection.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.353.

Grambo, Rebecca L. Bear: A Celebration of Power and Beauty. Burlington, Vermont: Verve, 2000, p.67.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 383.

On View

On view