Skip to main content

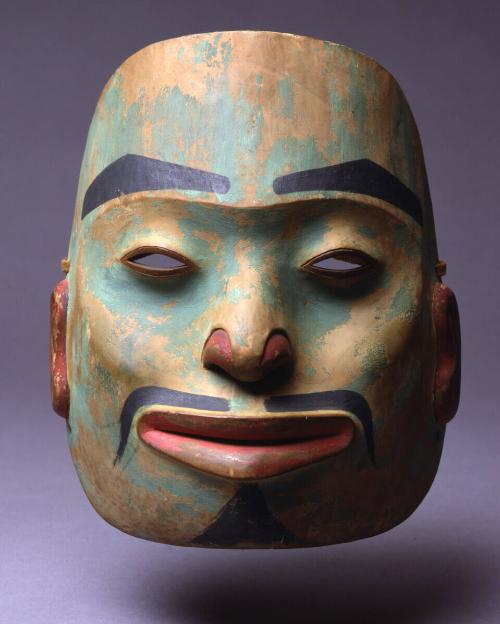

The mask-like face of the bird is adapted to the end of the dish in a manner that maximizes the sculptural effect inherent in the bulging dish form, and little additional relief is required to delineate the features of the bird's large-eyed face. The short, stout beak and lip lines are fairly straight, possibly indicating a raven, though a number of other straight-beaked birds that are crests of Tlingit clans could be represented, including seagull, murrelet, ouzel, petrel, merganser, or others. Only the original clan owners could identify with certainty the intended bird species. The leading edge of each wing begins as a subtle ridge, quickly becoming wider as it sweeps back along the sides. The tips of the wings finish off as angular U-shapes at the back of the dish, parallel to the extended tail feathers. Long, angular ovoids and square-cornered U-shapes are carved into the surface of the wings and tail, and similar design elements fill the area below the wings all the way around. The angular character of these forms and the minimal V-cuts and relief areas imply that the artist learned from the old tradition, and that the dish is probably from the early 19th century. The sculpture of the bird's face is well within the parameters of Tlingit style, pointed out by the large, slightly domed eyes with short, wide open eyelids, square eyebrow corners, minimal nostril, and rounded, naturalistic curve to the ridge of the beak.

Most grease dishes and other food-containing vessels are commonly wider than they are tall, facilitating not only access to what is within them in use, but their initial creation as well. The greater depth of this compact bowl, as well as the deep undercutting of the rim and rounded sides, presented a considerable additional challenge to the adz, knife, hands, and experience of its skilled maker. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Provenance George Terasaki, New York City

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert T. Masterpieces of American Indian Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995, p.81.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.380.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 417.

Culture

Tlingit

Bowl

Date1820-1860

MediumAlder, paint

DimensionsOverall: 5 1/4 × 5 3/4 × 9 1/4 in. (13.3 × 14.6 × 23.5 cm)

Object numberT0198

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextProportionately tall for this type of dish, the core form of this vessel is based on a traditional oval dish type that seems to curl inward like a dried-up gumboot, or black chiton, a small intertidal gastropod the Tlingits savor as a delicacy. Many existing bowls in this shape are relief-carved over their entire surface in flat-design formlines, but this one has been conceived with protruding sculptural developments in the form of a bird's beak, wings, and tail. The rim of the dish is quite wide, embellished with crisply-cut transverse grooves, and very dynamic in the way it sweeps high over the tall ends of the dish and down in a heavily tilted arc along the sides. As in related examples, the grooving on the dish rim may represent a skeuomorphic reference to the spruce root wrapped rims of folded and sewn birchbark dishes from the interior.The mask-like face of the bird is adapted to the end of the dish in a manner that maximizes the sculptural effect inherent in the bulging dish form, and little additional relief is required to delineate the features of the bird's large-eyed face. The short, stout beak and lip lines are fairly straight, possibly indicating a raven, though a number of other straight-beaked birds that are crests of Tlingit clans could be represented, including seagull, murrelet, ouzel, petrel, merganser, or others. Only the original clan owners could identify with certainty the intended bird species. The leading edge of each wing begins as a subtle ridge, quickly becoming wider as it sweeps back along the sides. The tips of the wings finish off as angular U-shapes at the back of the dish, parallel to the extended tail feathers. Long, angular ovoids and square-cornered U-shapes are carved into the surface of the wings and tail, and similar design elements fill the area below the wings all the way around. The angular character of these forms and the minimal V-cuts and relief areas imply that the artist learned from the old tradition, and that the dish is probably from the early 19th century. The sculpture of the bird's face is well within the parameters of Tlingit style, pointed out by the large, slightly domed eyes with short, wide open eyelids, square eyebrow corners, minimal nostril, and rounded, naturalistic curve to the ridge of the beak.

Most grease dishes and other food-containing vessels are commonly wider than they are tall, facilitating not only access to what is within them in use, but their initial creation as well. The greater depth of this compact bowl, as well as the deep undercutting of the rim and rounded sides, presented a considerable additional challenge to the adz, knife, hands, and experience of its skilled maker. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Provenance George Terasaki, New York City

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert T. Masterpieces of American Indian Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995, p.81.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.380.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 417.

On View

Not on view