Skip to main content

Among the Tlingit, however, a very different association is made with what appears to be essentially the same tool. Tlingit atlatls, of which perhaps twelve existing examples can be found, seem to have been made only in the 18th and very early 19th centuries, judging by the characteristics of their usually extensive sculptural and two-dimensional decoration. (c.f. Holm 1988, p. 282; Wardwell 1996, pp.218-223) Perhaps the most significant distinction is that the Tlingit versions of this object, which otherwise could have great ergonomic potential, are almost uncomfortable to hold, let alone use as they were intended (Holm 1988, p. 282). In some examples, such as this one, the small pin that would hold the feathered end of the throwing dart in place is in fact at the wrong angle to do so effectively. The carved imagery of Tlingit atlatls is usually very shamanic in nature. Taken as a whole, these circumstances suggest that the Tlingit version of this hunting weapon relied more on the efficacy of the spiritual assistance and power represented in the carved embellishments than on the functionality of the physical object. These were apparently employed not by dedicated hunters of animal game, but by the spiritual warriors of the unseen world, the Tlingit shamans, against those non-physical forces with which they had to contend in order to cure illness and provide their specialized variety of insight into the events of the physical world.

The relief-carving on this atlatl is elegant and masterful, both in sculpture and flat design. A tiny face carved into the snout of the terminal head at the bottom of the atlatl connects to its body relief-carved beneath the monster's jaw on the other side of the weapon. Four small, round glass trade beads have been inlayed into two pairs of flat-design inner ovoids, giving a depth and glow to those areas. It is possible that these arrived on the northern coast via Native trade, before direct contact by Euro-Americans brought trade beads in great numbers. These characteristics suggest that this atlatl could have been made very early, as the style of its creation implies, perhaps as early as 1750 (or before). (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

ProvenancePrivate collection, England; Christie's, London, December 8, 1992, lot 153

BibliographyChristie's. December 8, 1992, lot 153.

"Auction Block." American Indian Art Magazine. Vol.18, No.3 (Summer 1993): 27.

Vincent, Gilbert T. Masterpieces of American Indian Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995, p.87.

Wardwell, Allen. Tangible Visions: Northwest Coast Shamanism and its Art. New York: Monacelli Press/Corvus Press, 1996, pp.222-223, fig.320 - two views.

Perriot, Francoise, and Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, Somogy edition d'Art, 1999, p. 136, fig. 111.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.362.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 400.

Culture

Tlingit

Atlatl

Date1750-1800

DimensionsOverall: 1 1/2 × 1 × 15 in. (3.8 × 2.5 × 38.1 cm)

Object numberT0218

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextThe atlatl, a Nahuatl word for a throwing board or stick, was used by the Aleut, Alutiq (Pacific Eskimo), and Yup'ik to propel a weighted dart about three feet long, at a much greater force than could be done with one's arm alone. The throwing stick increases the leverage and acceleration inherent in the hunter's armstroke. They are marvels of ergonomic design, sculpted to fit the hand so effortlessly that not a bone of muscle is it of place when holding one, due to their non-linear and asymmetrical form. The hole in the atlatl is for the index finger, which provides a focus for aiming the projectile. These atlatls are seldom decorated more than to a simple, straightforward degree. Due to their efficiency, they have been used for hunting up until recent times.Among the Tlingit, however, a very different association is made with what appears to be essentially the same tool. Tlingit atlatls, of which perhaps twelve existing examples can be found, seem to have been made only in the 18th and very early 19th centuries, judging by the characteristics of their usually extensive sculptural and two-dimensional decoration. (c.f. Holm 1988, p. 282; Wardwell 1996, pp.218-223) Perhaps the most significant distinction is that the Tlingit versions of this object, which otherwise could have great ergonomic potential, are almost uncomfortable to hold, let alone use as they were intended (Holm 1988, p. 282). In some examples, such as this one, the small pin that would hold the feathered end of the throwing dart in place is in fact at the wrong angle to do so effectively. The carved imagery of Tlingit atlatls is usually very shamanic in nature. Taken as a whole, these circumstances suggest that the Tlingit version of this hunting weapon relied more on the efficacy of the spiritual assistance and power represented in the carved embellishments than on the functionality of the physical object. These were apparently employed not by dedicated hunters of animal game, but by the spiritual warriors of the unseen world, the Tlingit shamans, against those non-physical forces with which they had to contend in order to cure illness and provide their specialized variety of insight into the events of the physical world.

The relief-carving on this atlatl is elegant and masterful, both in sculpture and flat design. A tiny face carved into the snout of the terminal head at the bottom of the atlatl connects to its body relief-carved beneath the monster's jaw on the other side of the weapon. Four small, round glass trade beads have been inlayed into two pairs of flat-design inner ovoids, giving a depth and glow to those areas. It is possible that these arrived on the northern coast via Native trade, before direct contact by Euro-Americans brought trade beads in great numbers. These characteristics suggest that this atlatl could have been made very early, as the style of its creation implies, perhaps as early as 1750 (or before). (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"Art Des Indiens D'Amerique Du Nord Dans La Collection D'Eugene Thaw," Mona Bismarck Foundation, Paris, France, Somogy Editions D'Art, January 21, 2000 - March 18, 2000.

ProvenancePrivate collection, England; Christie's, London, December 8, 1992, lot 153

BibliographyChristie's. December 8, 1992, lot 153.

"Auction Block." American Indian Art Magazine. Vol.18, No.3 (Summer 1993): 27.

Vincent, Gilbert T. Masterpieces of American Indian Art. New York: Harry Abrams, 1995, p.87.

Wardwell, Allen. Tangible Visions: Northwest Coast Shamanism and its Art. New York: Monacelli Press/Corvus Press, 1996, pp.222-223, fig.320 - two views.

Perriot, Francoise, and Slim Batteux, trans. Arts des Indiens d'Amerique du Nord: Dans la Collection d'Eugene et Clare Thaw. Paris, Somogy edition d'Art, 1999, p. 136, fig. 111.

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.362.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 400.

On View

Not on viewc. 1795-1820

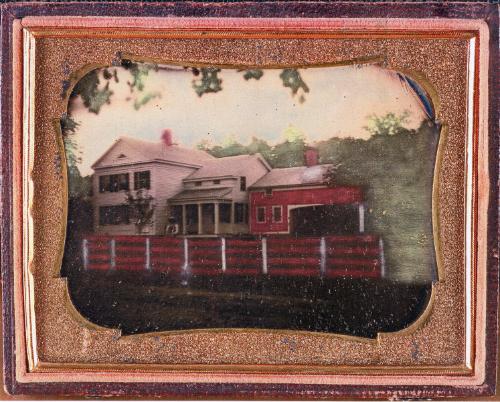

c. 1850-1859

c. 1907

c. 1890-1910

c. 1940-1949