Skip to main content

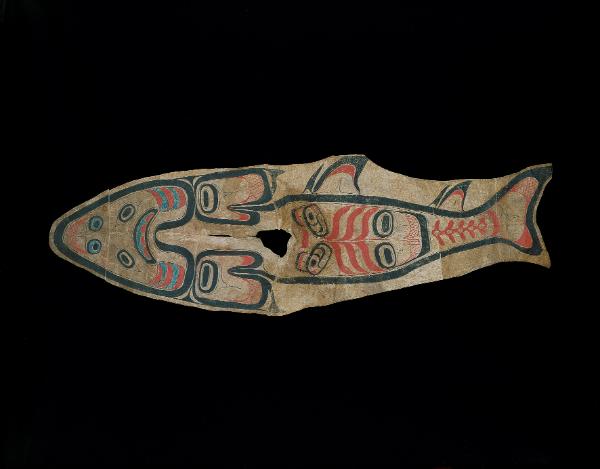

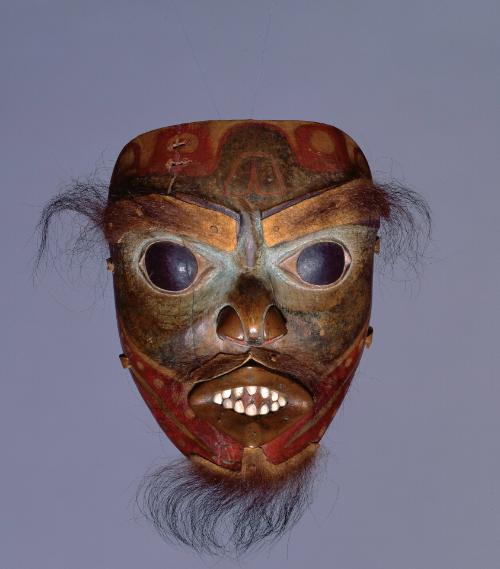

The head and pectoral fins of the creature are painted on the rounded end, which would likely hang down the front. The common Northwest Coast convention for representing a shark or dogfish is to center the face on the downturned mouth (found on the creature's underside), and to conceptually bring the eyes around to their unnatural but appropriate position above it. Crescent shapes alternating in red and blue define the gill slits of the shark, one of its main identifying characteristics. The body of the shark extends down the back of the cape and terminates in the creature's tail. The top of the body profile is shown with a pair of dorsal fins and their small spines, as well as the larger lobe of the heterocercal tail.

The painter of this design also did the painting on a well-known skin apron once in the Burke Museum in Seattle, representing two killer whales in profile. (c.f. Inverarity 1950, p.62). The style of painting- a somewhat unorthodox version of the formline tradition- indicates a late19th century origin. Each of the main design sections, the head, pectoral fins, and body, are delineated by a single encompassing black formline, rather than being composed of a small complex of formline patterns in each area. The mouth and eyes, the ovoids in the base of each pectoral fin, and the design elements in the body area are floating free of the main black formlines and are not integrated into the network of design elements as is always the case in older examples of the Northwest Coast tradition. The consistency of the black formlines and the thin finelines in either color points to a real familiarity with the older conventions, which have been liberalized and reinterpreted somewhat in this highly original and visually successful composition. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceRalph C. Altman, Los Angeles, California; Taylor Museum (3985), Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1951

BibliographyGunther, Erna. indians of the Northwest Coast. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1951 (not ill.).

Walker Art Center. American Indian Art: Form and Tradition. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972, p. 132, cat. no. 470 (not ill.).

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.392.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 438.

Culture

Tlingit

Cape

Date1860-1880

DimensionsOverall: 67 × 23 3/4 in. (170.2 × 60.3 cm)

Object numberT0223

Credit LineLoan from the Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextLt. George T. Emmons noted among the kinds of articles found in the possessions of Tlingit shamans a certain type of poncho-like hide garment that was sometimes worn with the rest of a shaman's outfit, which included a headdress or hat, woven or skin apron, and necklace of bone or ivory rods. Painted skin shoulder capes such as this, however, were comparatively rare. The Tlingit name 'tukw was recorded for such a long oval skin with a slit in the middle for the wearer's head (Emmons 1991, p. 380). This painted shoulder cape bears the formline representation of either a shark or dogfish. Both are used as Tlingit crest emblems and the clan affiliation of this object is not known.The head and pectoral fins of the creature are painted on the rounded end, which would likely hang down the front. The common Northwest Coast convention for representing a shark or dogfish is to center the face on the downturned mouth (found on the creature's underside), and to conceptually bring the eyes around to their unnatural but appropriate position above it. Crescent shapes alternating in red and blue define the gill slits of the shark, one of its main identifying characteristics. The body of the shark extends down the back of the cape and terminates in the creature's tail. The top of the body profile is shown with a pair of dorsal fins and their small spines, as well as the larger lobe of the heterocercal tail.

The painter of this design also did the painting on a well-known skin apron once in the Burke Museum in Seattle, representing two killer whales in profile. (c.f. Inverarity 1950, p.62). The style of painting- a somewhat unorthodox version of the formline tradition- indicates a late19th century origin. Each of the main design sections, the head, pectoral fins, and body, are delineated by a single encompassing black formline, rather than being composed of a small complex of formline patterns in each area. The mouth and eyes, the ovoids in the base of each pectoral fin, and the design elements in the body area are floating free of the main black formlines and are not integrated into the network of design elements as is always the case in older examples of the Northwest Coast tradition. The consistency of the black formlines and the thin finelines in either color points to a real familiarity with the older conventions, which have been liberalized and reinterpreted somewhat in this highly original and visually successful composition. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

ProvenanceRalph C. Altman, Los Angeles, California; Taylor Museum (3985), Colorado Springs, Colorado, 1951

BibliographyGunther, Erna. indians of the Northwest Coast. Seattle: Seattle Art Museum, 1951 (not ill.).

Walker Art Center. American Indian Art: Form and Tradition. New York: E. P. Dutton, 1972, p. 132, cat. no. 470 (not ill.).

Vincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.392.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 438.

On View

Not on view