Skip to main content

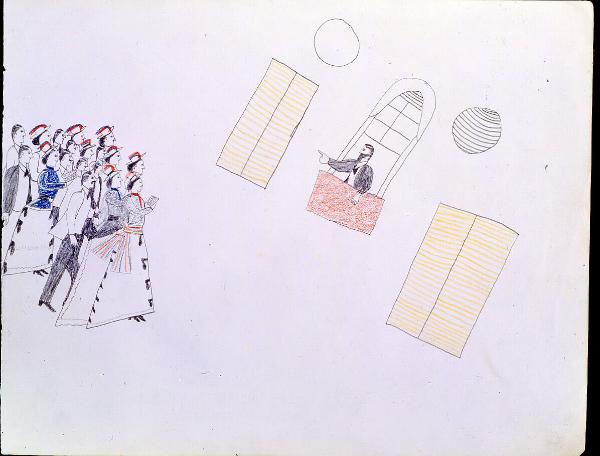

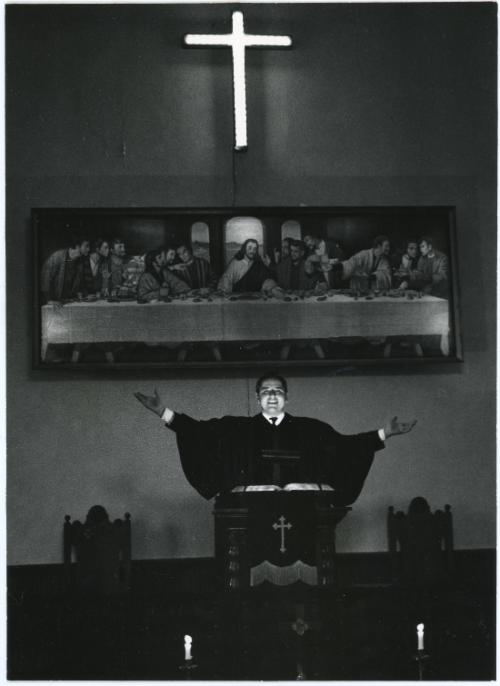

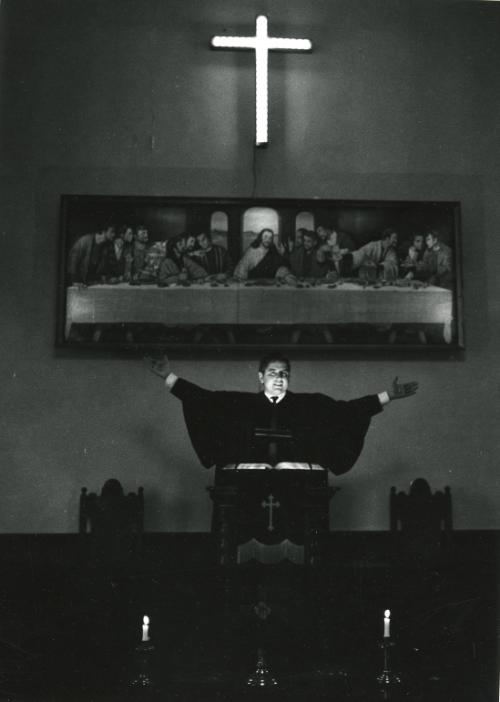

The conventions used by the Fort Marion artists are often highly specific as to place and placement of the scene. Recognizable places include interiors of schoolrooms, the Fort itself, nearby St. Augustine, Fort Sill Indian Territory, and various Kiowa camps and Sun Dance lodges (Berlo 1996a, pp. 52-53, figs. 2-4, pp. 128-129, cat. nos. 54-55, pp. 132-133, cat. no. 57, pp. 156-64, cat. nos. 79-88, pp. 176-177, cat. no. 102). The large amount of blank spaces seems to suggest the large architectural facade of a chapel, which encloses the preacher and his congregation.

Color is used sparingly in this drawing. Quick streaks of orange and blue mark the women's hats and scarves. One blue blouse is depicted. Yellow shutters and a red window or balcony ledge mark the implied facade to the right.

Other Fort Marion drawings depicting sermons show the rows of Native prisoners lined up in respectful attendance; such drawings are usually formal and rectilinear in their placement of figures. This asymmetrical drawing contrasts with the customary precision shown by Kiowa and Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) artists depicting the conventions of the Euro-American world (Berlo 1996a, p. 67, pl. 1, pp. 116-117, cat. nos. 44-45, pp. 138-141, cat. nos. 61-66). The Fort Marion artists often depicted themselves in non-Native garb, for at the prison they were required to wear military-issue garments; but here the artist is depicting non-Native men and women. The artist stands as outside observer, documenting a culture of which he is not a part.

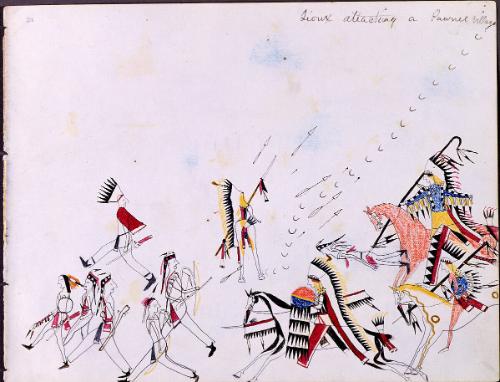

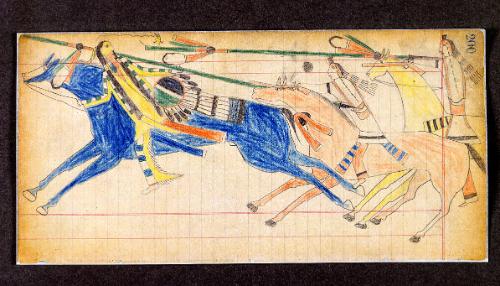

Like the Fort Marion drawing by Chief Killer (see p. 131), this work was done in a sketchbook that would have contained a dozen or more varied images. In some cases, the artists drew scenes that spread over two adjacent pages. Often, both sides of the page were filled with images. On the reverse of this page is drawn a scene of three Kiowa horsemen. Both drawings have been attributed by Joyce Szabo to the Kiowa artist Ohettoint, who was also known later in life by the name Charley Buffalo (Thaw Collection files).

Ohettoint was from a family of high ranking warriors and fine artists. His father was one of three 19th-century men to hold the distinguished name Tohausen, or Little Bluff (Greene 1996). While nothing is known of Ohettoint's work as an artist before his incarceration in 1875, he was a warrior who participated in attacks on white, for which he was sentenced to prison (Peterson 1971, pp. 161-170). At Fort Marion, he served as a baker as well as an artist. Most of his works remain unpublished. A sketchbook of twelve drawings, signed at the back "Ohettoint," exists today in the museum at the United States Military Academy, West Point. Hunting scenes, war parties, and other images of traditional life on the Southern Plains intermix with images of ships and Fort Marion prisoners in military garb being photographed (cf West Point Museum 15.604).

When their prison sentences were over in the spring of 1878, some men returned to the Southern Plains; others, including Ohettoint, stayed in the East for further schooling. He attended Hampton Institute in Virginia for several months, and was part of the first class of students at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in 1878, where he continued to draw (Peterson 1971). Ohettoint returned to the Kiowa reservation in 1880. There he labored as a teacher, farmer, and tribal policeman.

He also continued his artistry. The best known and most complex Kiowa pictorial tipi, "The Tipi With Battle Pictures," passed down through the Tohausen family. Ohettoint himself painted versions of it at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th (Ewers 1978 and Greene 1993). Yet his talents were overshadowed by those of his younger brother, Silver Horn (Haungooah, 1860-1940), who remains to this day the most prolific and innovative graphic artist on the Great Plains (cf Maurer 1992, pp. 162-165, figs. 115-119; Berlo 1996a, pp. 165-167, cat. nos. 89-94; Greene 2001). (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed. Janet Catherine Berlo)

Exhibition HistoryUntitled exhibit, The Rockwell Museum, Corning, NY, May 29, 1997 - January 8. 1998.

"American Treasures from the Fenimore Art Museum," Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, FL, February 20, 2004 - April 11, 2004.

ProvenanceDr. W. Simon, Baltimore, Maryland; Buchner Family, Germany; Unidentified museum, Germany; Horst Antes, Germany; Milford Holbrook, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Toby Herbst, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.126.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 126.

Attributed to

Ohettoint (Charley Buffalo)

(1852 - 1934, Kiowa)

Drawing - Church Service at Fort Marion

Date1875-1878

DimensionsFramed: 16 3/8 × 18 7/8 in. (41.6 × 47.9 cm)

Overall (Image Dimensions): 8 3/4 × 11 1/4 in. (22.2 × 28.6 cm)

Object numberT0084

Credit LineGift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextWithin the oeuvre of hundreds of drawings made by Southern Plains men incarcerated at Fort Marion, Florida, in the 1870s, this is a rather enigmatic work (see p. 131). On the left, a crowd of eighteen men and women stand attentively, facing toward the right. Two of the women hold open books, suggestive of prayer books of hymnals. Framed within a window, a preacher or orator gestures toward them.The conventions used by the Fort Marion artists are often highly specific as to place and placement of the scene. Recognizable places include interiors of schoolrooms, the Fort itself, nearby St. Augustine, Fort Sill Indian Territory, and various Kiowa camps and Sun Dance lodges (Berlo 1996a, pp. 52-53, figs. 2-4, pp. 128-129, cat. nos. 54-55, pp. 132-133, cat. no. 57, pp. 156-64, cat. nos. 79-88, pp. 176-177, cat. no. 102). The large amount of blank spaces seems to suggest the large architectural facade of a chapel, which encloses the preacher and his congregation.

Color is used sparingly in this drawing. Quick streaks of orange and blue mark the women's hats and scarves. One blue blouse is depicted. Yellow shutters and a red window or balcony ledge mark the implied facade to the right.

Other Fort Marion drawings depicting sermons show the rows of Native prisoners lined up in respectful attendance; such drawings are usually formal and rectilinear in their placement of figures. This asymmetrical drawing contrasts with the customary precision shown by Kiowa and Tsitsistas/Suhtai (Cheyenne) artists depicting the conventions of the Euro-American world (Berlo 1996a, p. 67, pl. 1, pp. 116-117, cat. nos. 44-45, pp. 138-141, cat. nos. 61-66). The Fort Marion artists often depicted themselves in non-Native garb, for at the prison they were required to wear military-issue garments; but here the artist is depicting non-Native men and women. The artist stands as outside observer, documenting a culture of which he is not a part.

Like the Fort Marion drawing by Chief Killer (see p. 131), this work was done in a sketchbook that would have contained a dozen or more varied images. In some cases, the artists drew scenes that spread over two adjacent pages. Often, both sides of the page were filled with images. On the reverse of this page is drawn a scene of three Kiowa horsemen. Both drawings have been attributed by Joyce Szabo to the Kiowa artist Ohettoint, who was also known later in life by the name Charley Buffalo (Thaw Collection files).

Ohettoint was from a family of high ranking warriors and fine artists. His father was one of three 19th-century men to hold the distinguished name Tohausen, or Little Bluff (Greene 1996). While nothing is known of Ohettoint's work as an artist before his incarceration in 1875, he was a warrior who participated in attacks on white, for which he was sentenced to prison (Peterson 1971, pp. 161-170). At Fort Marion, he served as a baker as well as an artist. Most of his works remain unpublished. A sketchbook of twelve drawings, signed at the back "Ohettoint," exists today in the museum at the United States Military Academy, West Point. Hunting scenes, war parties, and other images of traditional life on the Southern Plains intermix with images of ships and Fort Marion prisoners in military garb being photographed (cf West Point Museum 15.604).

When their prison sentences were over in the spring of 1878, some men returned to the Southern Plains; others, including Ohettoint, stayed in the East for further schooling. He attended Hampton Institute in Virginia for several months, and was part of the first class of students at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania in 1878, where he continued to draw (Peterson 1971). Ohettoint returned to the Kiowa reservation in 1880. There he labored as a teacher, farmer, and tribal policeman.

He also continued his artistry. The best known and most complex Kiowa pictorial tipi, "The Tipi With Battle Pictures," passed down through the Tohausen family. Ohettoint himself painted versions of it at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th (Ewers 1978 and Greene 1993). Yet his talents were overshadowed by those of his younger brother, Silver Horn (Haungooah, 1860-1940), who remains to this day the most prolific and innovative graphic artist on the Great Plains (cf Maurer 1992, pp. 162-165, figs. 115-119; Berlo 1996a, pp. 165-167, cat. nos. 89-94; Greene 2001). (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed. Janet Catherine Berlo)

Exhibition HistoryUntitled exhibit, The Rockwell Museum, Corning, NY, May 29, 1997 - January 8. 1998.

"American Treasures from the Fenimore Art Museum," Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, FL, February 20, 2004 - April 11, 2004.

ProvenanceDr. W. Simon, Baltimore, Maryland; Buchner Family, Germany; Unidentified museum, Germany; Horst Antes, Germany; Milford Holbrook, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Toby Herbst, Santa Fe, New Mexico

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.126.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 126.

On View

Not on viewc. 1915-1937

c. 1910-1920