Skip to main content

The Hasbrouck House had been built by Jonathan, third-generation descendant of Huguenot immigrants of 1677, on land his mother had purchased in 1749. Jonathan built the original section of rubble stone and soon thereafter expanded it twice between 1750 and 1770 to accommodate his family of seven children. Before the Revolution, he had become a prosperous merchant, mill owner, farmer, and militia officer. With the advent of war, he was given a colonel's rank in the state militia, a position he held until ill health caused his resignation in 1778. He died two years later not long before his house would be appropriated for Washington's use.

Martha and George found little privacy and comfort in the one-story, eight room house. Three or four aides, servants, and frequent visitors were jammed into the incommodious rooms sparsely furnished and probably very chilly in winter, while in the temporary buildings near the house the general's "Culinary Corps" did its best to supply his table copiously from a stable of livestock and Mrs. Hasbrouck's garden in season. While the Washington's had brought some furniture with them from their last headquarters in Philadelphia, they dined with their guests seated on camp stools, bedded their VIP guests in Martha's sitting room, and sought a modicum of privacy in the midst of turmoil that engulfed the headquarters scene. "A dreary mansion...among these rugged and dreary mountains," Washington commented as he and Martha left for Mount Vernon after sixteen and a half months of duty in the Hudson Highlands.

The Hasbrouck family reoccupied their house, and, around 1800, began to appreciate its historical significance. They carved inscriptions into exposed timbers inside the building and were not hesitant to keep the legacy alive locally. But Jonathan Jr. suffered financial reverses in the Panic of 1837 causing him to borrow $2,000 from the U.S. Deposit Fund Commission. Nine years later, he defaulted on the loan and lost his house that had been put up as collateral. No buyer of the property surfaced. Even though a citizens committee was formed and included no lesser a light than Washington Irving, funds could not be raised for its preservation, an idea simply too new to be accepted. Only the intervention of the legislature and Governor Hamilton Fish saved Hasbrouck House. The State reimbursed the Deposit Fund $2,391.02 and appropriated an additional $6,000 to buy the land to buffer the property and to restore the building. On July 4, 1850, General Winfield Scott came up the Hudson from West Point to raise old glory on the newly erected flag pole to fly over the first historic house museum in America.

The Headquarters has been subject to the ministrations of many historians and public spirited citizens for nearly a century and a half, longer than any other precious landmarks. Each interpretation was replaced by its successor without trace. What has remained through time, however, is the structure itself, the massive beams, the open fireplace, the small paned windows, and the other "witnesses" to Washington's occupancy. "The floor," the 1857 observer related, "has resounded to HIS tread, and the walls have echoed to the tone of HIS voice; HIS eyes have gazed through those narrow panes, and the silent beams have witnessed scenes memorable in history."

The house is the house no matter how we arrange its contents. The next generation of curators may strip it bare leaving the meaning of its "sacred precincts" to the visitor's imagination. Whatever the plan, Hasbrouck House is timber, masonry, and emotional association with George Washington. It is also a symbol of pioneer governmental support of historic preservation. As such it will continue to be revered and remembered just as it was as early as 1835 for being "one of the most interesting of the first and heroic age of our republic."

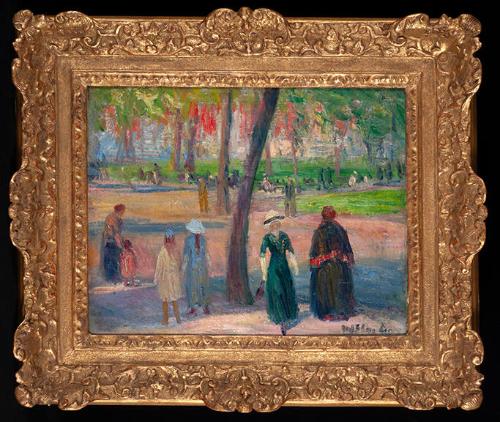

This view illustrates the house after it had become a state site. Part of the opening included raising the flag on the new flagpole and firing the cannon, visible on the front lawn. A variety of artists made paintings and prints of the house, DeGrailly creating one of the most picturesque with a developed foreground and the Hudson River visible in the background.

Attributed to

Victor De Grailly

(French, 1840 - 1870)

Related Person

George Washington

(1732 - 1799)

Washington's Headquarters at Newburgh

Date1861

MediumOil on canvas

DimensionsSight: 13 7/8 × 20 in. (35.2 × 50.8 cm)

Object numberN0394.1961

Credit LineCollection of the Fenimore Art Museum. Gift of Stephen C. Clark

Photograph by Richard Walker

Label TextThe advance party that was charged with finding and preparing a suitable headquarters and residence for Commander-in-Chief George Washington in the Hudson Valley late in the autumn of 1781 faced no easy task. Colonel David Humphreys, one of Washington's aides, was in Newburgh to select a facility near the Continental Army's encampment, warehouses, and other installations that had been established to hem the British in New York City while a peace treaty was being negotiated in Paris. The only place found suitable for the General, his staff and "Life Guard," and Mrs. Washington was widow Tryntje Hasbrouck's stone home "built in the Dutch fashion," a visitor commented, overlooking the Hudson River where the military ferry operated and quartermaster warehouses were situated. Mrs. Hasbrouck agreed to vacate herself, her furnishings, her family and her tenant, Mrs. Timothy Pickering, wife of the Quartermaster General, to allow General and Mrs. Washington unencumbered use of the property as long as required. After some indecision and delays, a kitchen, bunk room, stables, and other jerry-built structures were thrown up near by and the house was adapted to receive the General and his entourage on March 31, 1782.The Hasbrouck House had been built by Jonathan, third-generation descendant of Huguenot immigrants of 1677, on land his mother had purchased in 1749. Jonathan built the original section of rubble stone and soon thereafter expanded it twice between 1750 and 1770 to accommodate his family of seven children. Before the Revolution, he had become a prosperous merchant, mill owner, farmer, and militia officer. With the advent of war, he was given a colonel's rank in the state militia, a position he held until ill health caused his resignation in 1778. He died two years later not long before his house would be appropriated for Washington's use.

Martha and George found little privacy and comfort in the one-story, eight room house. Three or four aides, servants, and frequent visitors were jammed into the incommodious rooms sparsely furnished and probably very chilly in winter, while in the temporary buildings near the house the general's "Culinary Corps" did its best to supply his table copiously from a stable of livestock and Mrs. Hasbrouck's garden in season. While the Washington's had brought some furniture with them from their last headquarters in Philadelphia, they dined with their guests seated on camp stools, bedded their VIP guests in Martha's sitting room, and sought a modicum of privacy in the midst of turmoil that engulfed the headquarters scene. "A dreary mansion...among these rugged and dreary mountains," Washington commented as he and Martha left for Mount Vernon after sixteen and a half months of duty in the Hudson Highlands.

The Hasbrouck family reoccupied their house, and, around 1800, began to appreciate its historical significance. They carved inscriptions into exposed timbers inside the building and were not hesitant to keep the legacy alive locally. But Jonathan Jr. suffered financial reverses in the Panic of 1837 causing him to borrow $2,000 from the U.S. Deposit Fund Commission. Nine years later, he defaulted on the loan and lost his house that had been put up as collateral. No buyer of the property surfaced. Even though a citizens committee was formed and included no lesser a light than Washington Irving, funds could not be raised for its preservation, an idea simply too new to be accepted. Only the intervention of the legislature and Governor Hamilton Fish saved Hasbrouck House. The State reimbursed the Deposit Fund $2,391.02 and appropriated an additional $6,000 to buy the land to buffer the property and to restore the building. On July 4, 1850, General Winfield Scott came up the Hudson from West Point to raise old glory on the newly erected flag pole to fly over the first historic house museum in America.

The Headquarters has been subject to the ministrations of many historians and public spirited citizens for nearly a century and a half, longer than any other precious landmarks. Each interpretation was replaced by its successor without trace. What has remained through time, however, is the structure itself, the massive beams, the open fireplace, the small paned windows, and the other "witnesses" to Washington's occupancy. "The floor," the 1857 observer related, "has resounded to HIS tread, and the walls have echoed to the tone of HIS voice; HIS eyes have gazed through those narrow panes, and the silent beams have witnessed scenes memorable in history."

The house is the house no matter how we arrange its contents. The next generation of curators may strip it bare leaving the meaning of its "sacred precincts" to the visitor's imagination. Whatever the plan, Hasbrouck House is timber, masonry, and emotional association with George Washington. It is also a symbol of pioneer governmental support of historic preservation. As such it will continue to be revered and remembered just as it was as early as 1835 for being "one of the most interesting of the first and heroic age of our republic."

This view illustrates the house after it had become a state site. Part of the opening included raising the flag on the new flagpole and firing the cannon, visible on the front lawn. A variety of artists made paintings and prints of the house, DeGrailly creating one of the most picturesque with a developed foreground and the Hudson River visible in the background.

On View

Not on view