Skip to main content

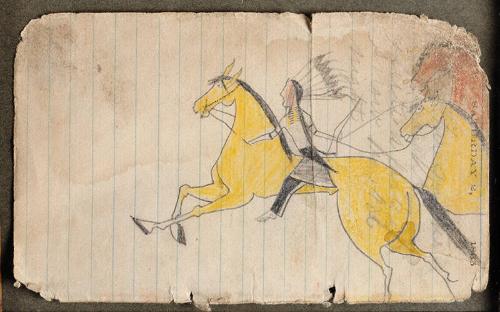

After the mid-19th century, the streamlined abstraction of these drawings was enriched by a more liberal use and variety of colors. The attention to significant detail increased as reflected in facial markings, clothing, and hairstyles, by which the members of warrior societies and of other tribes were distinguished.

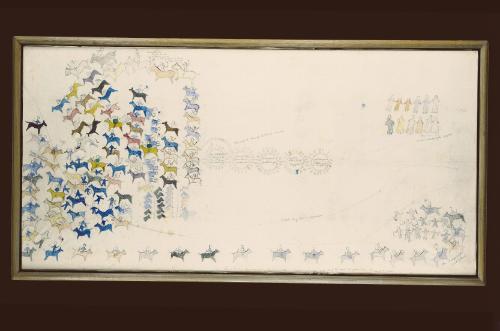

Continuity as well as change is evident in this art style since the 1870s whenthe buffalo herds disappeared, white settlers arrived in increasing numbers, and the Native people were confined to reservstions by military force. Pictographic art retained its vigor and dynamic quality while art media, themes, and functions of the drawings changed. Buffalo skins and native pigments gave way to muslin, paper, crayons, and other imported color pigments. Themes related to hunting and warfare were gradually replaced by reminiscences of public celebrations and sacred rituals. Old war veterans still recorded their adventures on sheets of muslin to decorate interior walls of their frame houses, and their production increased considerably when they discovered in them a source of income from the white newcomers. Many of these colorful compositions were commissioned by military officers, who used them to decorate their own rooms. Intended for a non-Native audience, these later picture narratives were often more generalized reflections of bygone times instead of autobiographical records. The drawings on this particular muslin belong somewhere in the development sketched here. They were undoubtedly made by Standing Rock Sioux artists in the 1880s, comparable as they are to other examples from that locality in the same period. Dorothy Dunn described a muslin drawing that she considered typically Sioux, "a spirited panorama of horse galloping in two ranks, one above the other, with riders in war trappings chasing enemy horses and counting coup upon captives." She could have been writing about this particular artwork. In addition to two parallel rows of horsemen, this muslin shows at the right still a third row of three horsemen and three individuals standing near a tipi.

Two artists have been at work here. Most of the vignettes were drawn by artist A, who adhered closely to the old traditional style of gently galloping, robust monochrone horses with small heads. Their uniform size and basically identical pose suggest the use of stencils, something that has been noted in other drawings from Standing Rock. Ornamental details on horses and riders are restricted to objects and decorations that are significant in the story line.

Artist B aimed at more realism and more action in his drawings. Most of his vignettes are located in the right-hand portion of the muslin. His horses and human figures are of smaller size, but they share with the other vignettes an interest in details. At first sight, the muslin seems to be merely a colorful cavalcade made to satisfy a non-Native clientele. Almost all of the horses have riders, so the popular reference to horse raids is absent. Neither glyphs nor written names identify the warriors. The general style is indeed typical of a piece from the early Reservation period.

Nevertheless, close inspection strongly suggests that the vignettes relate to a sequence of diverse exploits at different times. As such, the artists give evidence of narrating personal experiences in a composition that resembles those on traditional buffalo robes and tipi linings.

In three scenes, the same warrior plays a role, indicated by his full headdress of black feathers around a crest of eagle tailfeathers, a long sash trailing behind him, and scarves tied around his knees and ankles. This regalia identifies him as a member of the Miwatani Society. To the far left, this warrior is at the head of a group of eight horses, one of which has lost its rider. Though he may be the leader of this war party, the record also includes an outstanding warrior, as indicated by his scalp-fringe shirt. The second event in which the Miwatani man was involved is pictured rught behind this war party. Here we see him and some of his friends in pursuit of two Apsaalooke (Crow) men. One of them is identified as such by a green capote, while the other shows the pompadour hairdo, face paint, and striped breechcloth as generic details of the Crow. Behind the Miwatani man on his blue horse rides a member of the Horse Dreamers Society, identified by the buffalo mask and the painted decoration of his yellow horse.

A Horse Dreamer, maybe the same man, is riding beside the Miwatani man in the next scene of what looks like a parade. Notice that the two men seemed to have swapped thier horses. Were they perhaps close friends? This question comes up again while trying to read the separate incidents pictured on the right side of the muslin. Twice we see the two friends riding double, once on a yellow mule. While riding a red horse, one of them carries a shield decorated with a buffalo mask, possibly related to the buffalo masks used by the horse of the Horse Dreamer mentioned before. In addition to several hostile encounters with Apsaalooke (Crow), artist B also refers to a courtship or marriage proposal. A horse rider wrapped in a courting blanket arrives at a tipi. There he is pictured again in conversation with a women, while another man--perhaps his friend--is standing nearby.

It should not be considered accidental that on this muslin decorated by two artists we find repeated references to two friends. This observation seems to confirm an earlier suggestion that this is a narrative in the autobiographical tradition. Although the influenves of white man's patronage and culture changes are evident, the warrior artists who made the drawings were able to express themselves in a traditional style and communicate their own cultural values.

Several well-known warrior artists resided at the Standing Rock Reservation in the late 19th century. Probably the most prolific artist was No-Two-Horns, but similar drawings and paintings were created by One Bull, Swift Dog, Sitting Crow, and Jaw. Particularly, the style of Jaw's work closely resembles that of Artist A on this muslin. Further stylistic and comparative analysis may well lead to the identification of the two friends who recorded their adventures on this fascinating wall decoration. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"American Treasures from the Fenimore Art Museum," Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, FL, February 20, 2004 - April 11, 2004.

American Indian Art from The Fenimore Art Museum: The Thaw Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, May 9, 2017 - October 8, 2017.

ProvenanceMajor James A. Mclaughlin, Fort Yates, North Dakota; Usher L. Burdick, Fargo, North Dakota; Jonathan Holstein, Cazenovia, New York

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.142-143.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 148.

Culture

Lakota (Teton Sioux)

War Record

Datec. 1880

DimensionsOverall: 36 × 316 in. (91.4 × 802.6 cm)

Object numberT0371

Credit LineGift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw

Photograph by John Bigelow Taylor, NYC

Label TextThe drawings on this muslin sheet are representative of the pictographic art style used by Plains Indian men in recording their war exploits. Proclaiming their achievements, the conventionalized images of battle prowess and horse raids decorated skin garments, tipi covers, and tipi linings of these warrior-artists.After the mid-19th century, the streamlined abstraction of these drawings was enriched by a more liberal use and variety of colors. The attention to significant detail increased as reflected in facial markings, clothing, and hairstyles, by which the members of warrior societies and of other tribes were distinguished.

Continuity as well as change is evident in this art style since the 1870s whenthe buffalo herds disappeared, white settlers arrived in increasing numbers, and the Native people were confined to reservstions by military force. Pictographic art retained its vigor and dynamic quality while art media, themes, and functions of the drawings changed. Buffalo skins and native pigments gave way to muslin, paper, crayons, and other imported color pigments. Themes related to hunting and warfare were gradually replaced by reminiscences of public celebrations and sacred rituals. Old war veterans still recorded their adventures on sheets of muslin to decorate interior walls of their frame houses, and their production increased considerably when they discovered in them a source of income from the white newcomers. Many of these colorful compositions were commissioned by military officers, who used them to decorate their own rooms. Intended for a non-Native audience, these later picture narratives were often more generalized reflections of bygone times instead of autobiographical records. The drawings on this particular muslin belong somewhere in the development sketched here. They were undoubtedly made by Standing Rock Sioux artists in the 1880s, comparable as they are to other examples from that locality in the same period. Dorothy Dunn described a muslin drawing that she considered typically Sioux, "a spirited panorama of horse galloping in two ranks, one above the other, with riders in war trappings chasing enemy horses and counting coup upon captives." She could have been writing about this particular artwork. In addition to two parallel rows of horsemen, this muslin shows at the right still a third row of three horsemen and three individuals standing near a tipi.

Two artists have been at work here. Most of the vignettes were drawn by artist A, who adhered closely to the old traditional style of gently galloping, robust monochrone horses with small heads. Their uniform size and basically identical pose suggest the use of stencils, something that has been noted in other drawings from Standing Rock. Ornamental details on horses and riders are restricted to objects and decorations that are significant in the story line.

Artist B aimed at more realism and more action in his drawings. Most of his vignettes are located in the right-hand portion of the muslin. His horses and human figures are of smaller size, but they share with the other vignettes an interest in details. At first sight, the muslin seems to be merely a colorful cavalcade made to satisfy a non-Native clientele. Almost all of the horses have riders, so the popular reference to horse raids is absent. Neither glyphs nor written names identify the warriors. The general style is indeed typical of a piece from the early Reservation period.

Nevertheless, close inspection strongly suggests that the vignettes relate to a sequence of diverse exploits at different times. As such, the artists give evidence of narrating personal experiences in a composition that resembles those on traditional buffalo robes and tipi linings.

In three scenes, the same warrior plays a role, indicated by his full headdress of black feathers around a crest of eagle tailfeathers, a long sash trailing behind him, and scarves tied around his knees and ankles. This regalia identifies him as a member of the Miwatani Society. To the far left, this warrior is at the head of a group of eight horses, one of which has lost its rider. Though he may be the leader of this war party, the record also includes an outstanding warrior, as indicated by his scalp-fringe shirt. The second event in which the Miwatani man was involved is pictured rught behind this war party. Here we see him and some of his friends in pursuit of two Apsaalooke (Crow) men. One of them is identified as such by a green capote, while the other shows the pompadour hairdo, face paint, and striped breechcloth as generic details of the Crow. Behind the Miwatani man on his blue horse rides a member of the Horse Dreamers Society, identified by the buffalo mask and the painted decoration of his yellow horse.

A Horse Dreamer, maybe the same man, is riding beside the Miwatani man in the next scene of what looks like a parade. Notice that the two men seemed to have swapped thier horses. Were they perhaps close friends? This question comes up again while trying to read the separate incidents pictured on the right side of the muslin. Twice we see the two friends riding double, once on a yellow mule. While riding a red horse, one of them carries a shield decorated with a buffalo mask, possibly related to the buffalo masks used by the horse of the Horse Dreamer mentioned before. In addition to several hostile encounters with Apsaalooke (Crow), artist B also refers to a courtship or marriage proposal. A horse rider wrapped in a courting blanket arrives at a tipi. There he is pictured again in conversation with a women, while another man--perhaps his friend--is standing nearby.

It should not be considered accidental that on this muslin decorated by two artists we find repeated references to two friends. This observation seems to confirm an earlier suggestion that this is a narrative in the autobiographical tradition. Although the influenves of white man's patronage and culture changes are evident, the warrior artists who made the drawings were able to express themselves in a traditional style and communicate their own cultural values.

Several well-known warrior artists resided at the Standing Rock Reservation in the late 19th century. Probably the most prolific artist was No-Two-Horns, but similar drawings and paintings were created by One Bull, Swift Dog, Sitting Crow, and Jaw. Particularly, the style of Jaw's work closely resembles that of Artist A on this muslin. Further stylistic and comparative analysis may well lead to the identification of the two friends who recorded their adventures on this fascinating wall decoration. (From the Catalog of the Thaw Collection of American Indian Art, 2nd ed.)

Exhibition History"American Treasures from the Fenimore Art Museum," Society of the Four Arts, Palm Beach, FL, February 20, 2004 - April 11, 2004.

American Indian Art from The Fenimore Art Museum: The Thaw Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, May 9, 2017 - October 8, 2017.

ProvenanceMajor James A. Mclaughlin, Fort Yates, North Dakota; Usher L. Burdick, Fargo, North Dakota; Jonathan Holstein, Cazenovia, New York

BibliographyVincent, Gilbert et al. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2000, p.142-143.

Fognell, Eva and Alexander Brier Marr, eds. Art of the North American Indians: The Thaw Collection at the Fenimore Art Museum, 2nd ed. Cooperstown, New York: Fenimore Art Museum, 2016, p. 148.

On View

Not on view